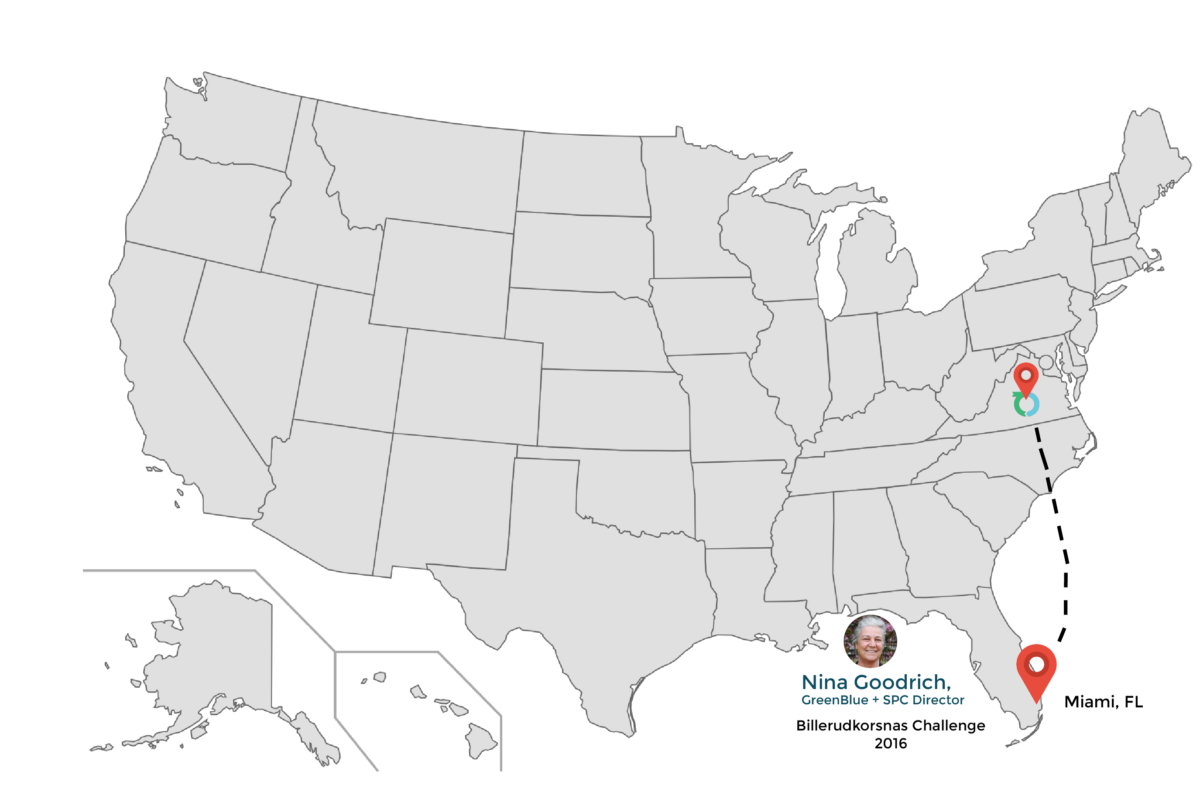

I recently had the opportunity to participate in the Billerudkorsnas Challenge 2016 Event in Miami, Florida. The event brought together decision-makers, scientists, and representatives from the business community to discuss wise solutions to the problems of today and tomorrow. But the meeting’s guest of honor was the boat Tara and her crew.

The marine research ship Tara had docked in Miami for this event and was preparing to head out on a two-year voyage to study coral reefs in the Pacific. Tara Expeditions is a sea research institute that is sailing all over the world to investigate the conditions in our oceans. Recent research results from previous expeditions have been published in both Science and in Nature.

The history of Tara is fascinating. The ship was built by a Swedish explorer who wanted to follow the route of an explorer from 1895 who sailed his ship into the Artic Sea ice to prove that the currents would take him across the North Pole and release him on the other side. Tara repeated the voyage in 2006, and spent 507 days passing within 100 km of the North Pole. The boat’s crew measured the thickness of the sea ice throughout the journey and sampled the water. Because of warming ocean temperatures and the movement of the currents, Tara’s voyage was much faster than the 1895 voyage. Results from recent expeditions have been published in both Science and in Nature.

In 2011 Tara began sampling for plastic in the ocean. During a voyage this year from France to Miami, plastic was found every day in every sample taken. Guests at the Challenge event learned in a lecture from Romain Troublé, executive director of Tara Expedition Foundation, that algae and other marine organisms can attach themselves to the microplastic and travel much farther than was possible before. The plastic pieces become rafts and allow the marine organisms to hitchhike to distant destinations. It is currently unknown what effect this might have for the transfer of plants, viruses and bacteria across ocean regions.

Microscopic organisms make up 98% of the life in the ocean. They capture carbon dioxide and produce half of the world’s oxygen. During the Tara Oceans expedition the scientists collected samples of plankton from major oceanic regions, identified 100,000 new species of life in the ocean and compiled their genetic material into a resource that is now available to scientists all over the world. We tend to think of the rainforest as a source of new genetic biodiversity but the oceans are equally rich and largely unexplored.

The Tara Pacific expedition will be studying coral reefs and their biodiversity until 2018. Coral reefs have been significantly affected by human activities, global warming, and ocean acidification. This expedition hopes to study this fragile ecosystem and learn how to preserve it.

The most hopeful observation that was shared was that when microorganisms attach themselves to plastic the plastic gets heavier and eventually sinks. The current sampling for plastic in the oceans can only account for a small percentage of the plastic that we are dumping in the ocean each year. If we can stop the land-based pollution the ocean may be able to heal the damage we have done in a period of 50 years.

To follow Tara on its journey, visit http://oceans.taraexpeditions.org.