For many of us, spring cleaning is an opportunity to give our homes a deep-clean and tackle the grimy spots that don’t make it into our weekly routine. Kitchen cabinets, ovens, the outsides of windows, and the insides of cleaning appliances like dishwashers and washing machines can accumulate dirt and other crud that goes unnoticed for months or even years, so it’s important to take the time each year to make sure they get the attention they need.

But not all of the cleaning products we use are the best for our health, the environment, or the health of others in our homes (like kids and pets). Recent studies have found that conventional cleaning products can harm lung function as much as smoking cigarettes, and volatile organic chemicals in cleaning and other household products now contribute to outdoor air pollution as much as cars. Many cleaning products contain chemicals that can cause asthma, which is especially a concern for products used in schools or around kids since about one in ten kids has asthma and asthma is a leading cause of school absenteeism.

Refusing to clean isn’t a realistic option. Never mind the dirt (and potentially resentful family members or roommates) – household dust itself can contain hazardous chemicals, such as halogenated flame retardants from furniture or electronics and phthalates from vinyl flooring. So what can you do to keep your home sparkling while avoiding exposure to hazardous chemicals? Given the prevalence of greenwashing and the fact that most cleaning products don’t currently disclose all of their ingredients (though that is changing), it can seem daunting to make an informed decision.

Some people choose to make their own cleaning products, which in some cases can be a good (and frugal) option. But proceed with caution – some ingredients in homemade cleaning products can also be hazardous to your health. Borax, a common ingredient in homemade laundry detergent recipes, is associated with reproductive, developmental, and neurological hazards, and some essential oils, often used to provide a natural fragrance, can cause sensitization and allergic reactions and can be harmful to pets. Plus, some combinations of ingredients that are safe and effective cleaners on their own become ineffective when combined. For example, when baking soda and vinegar are mixed, they neutralize each other, reducing cleaning effectiveness, and mixing vinegar with castile soap unsaponifies the soap, resulting in an oily, curdled mess.

If you’d rather leave cleaning product formulation to the experts, but want to ensure that the ingredients are safer for you, your kids, your pets, and the environment, look for products with the EPA Safer Choice label. EPA’s Safer Choice program certifies cleaning products that meet the Safer Choice Standard, and is backed up by EPA’s years of expertise in assessing chemicals and use of predictive models to assess hazards of chemicals that lack toxicity data. To achieve the Safer Choice certification, every intentionally added ingredient in a product, including proprietary mixtures and ingredients present at a very low concentration, must be reviewed by third-party experts to confirm that the ingredients are among the safest-in-class for people and the environment. Even if not intentionally added, known residuals from the manufacturing process present at concentrations above 0.01% must be reviewed, and residuals of concern must be reduced to the lowest feasible levels. The Safer Choice team also looks for negative synergies between ingredients in a product, to avoid reactions that could cause harm, and works with product manufacturers to support continuous improvement and innovation in the development of safer products.

Among other requirements, ingredients used in Safer Choice-certified products can’t include chemicals that are likely to cause cancer, alter genes or affect reproduction, or toxic chemicals that don’t break down in the environment and accumulate in our bodies and the food chain. Generally, no ingredients classified as skin or respiratory sensitizers (which may cause allergic reactions after repeat exposure) may be included. Overall, formulations must meet the volatile organic compound (VOC) content restrictions set by the Ozone Transport Commission and the California Air Resources Board in order to protect indoor and outdoor air quality. For products used outdoors, such as pressure washer concentrates, car washes, or boat washes, Safer Choice applies more stringent aquatic toxicity standards to ensure that products don’t hurt fish or other aquatic life. Plus, all products with the Safer Choice label must meet performance standards, meaning they perform at least as well as conventional products.

Among other requirements, ingredients used in Safer Choice-certified products can’t include chemicals that are likely to cause cancer, alter genes or affect reproduction, or toxic chemicals that don’t break down in the environment and accumulate in our bodies and the food chain. Generally, no ingredients classified as skin or respiratory sensitizers (which may cause allergic reactions after repeat exposure) may be included. Overall, formulations must meet the volatile organic compound (VOC) content restrictions set by the Ozone Transport Commission and the California Air Resources Board in order to protect indoor and outdoor air quality. For products used outdoors, such as pressure washer concentrates, car washes, or boat washes, Safer Choice applies more stringent aquatic toxicity standards to ensure that products don’t hurt fish or other aquatic life. Plus, all products with the Safer Choice label must meet performance standards, meaning they perform at least as well as conventional products.

Safer Choice certifies products for both home and business/institutional use, in a broad range of product categories to meet needs at home, work, and school. You can look for the label on everyday products like all-purpose cleaner, laundry detergent, and dish soap, as well as more specialized items such as appliance cleaners, descalers, and floor strippers that help you get through your spring cleaning checklist. You can even find the label on pet shampoos and bicycle lubricants. Fragrance free options are identified with a specific version of the Safer Choice label. A full listing of products with the Safer Choice certification is available on EPA’s website.

Cleaning may not be the most fun way to spend a beautiful spring Saturday, but fortunately, there are safer product options that will get the job done. Just look for the Safer Choice label and you will be on your way to a cleaner, healthier home.

Author: user

The Composting Collaborative gathered on January 21st at the US Composting Council’s annual conference in Atlanta. More than 70 members, including many first-time participants, congregated for a jam-packed afternoon of flashtalks, a thought-provoking discussion on organics measurement, and a workshop on design thinking applied to composting from the Food Well Alliance.

Traversing more than 8 topics, the flashtalks dove into a diversity of issues. To kick off the meeting, Brenda Platt from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance shared an analysis of the importance of home and community-scale composting in the broader organics recycling context. As a small-scale bike-powered hauler based in Athens, GA, Kristen Baskin of Let Us Compost provided a more personal experience of many of the tenets that Platt discussed and shared how Let Us Compost has experimented with loss leaders and creative pricing for commercial clients.

Pivoting towards topics relating to compostable packaging, Camilo Ferro of Renew Packaging discussed a host of challenges that compostable packaging face nationwide. Namely, Ferro highlighted the reality that as “bag bans” have been passed in cities and counties across the country, compostable film bags are often unintentionally subject to restrictions or fees intended for conventional plastic film bags. Lynn Dyer with the Foodservice Packaging Institutecontinued the dialogue on compostable packaging in her flashtalk, sharing high-level results of their recent study that examined the current state of composting infrastructure capable of diverting both food scraps and compostable packaging.

Ending flashtalks on the note of the critical role that measurement and data play, Nora Goldstein, BioCycle editor and Composting Collaborative founding partner, led the group through the most impactful findings discovered in BioCycle’s State of Organics Recycling in the U.S. Report, funded in part by a grant from the U.S. EPA to the Composting Collaborative. Beyond the interesting and valuable findings concerning the number of composting facilities, the size of active facilities, and the materials that they are processing, learnings from the data collection process were perhaps most revealing.

Unfortunately, over the course of multiple large-scale efforts by BioCycle to collect organics recycling data, it has become apparent that the ability for states to collect and synthesize organics recycling information is decreasing, despite the fact that residential organics collection programs and quantity of households with access to organics recycling are on the rise nationwide.

In brainstorming the metrics most important to different stakeholders in the composting supply chain, the Composting Collaborative laid groundwork for much of the organics measurement work slated for 2018, including facilitating discussions among state-level professionals responsible for reporting to better understand gaps, standardize definitions, and determine where data collection breaks down. This conversation will continue at the February 27-March 1 Measurement Matters Summit in Chattanooga, Tennessee and onward into spring and summer 2018 in Collaborative forums.

After exploring the influence of thoughtfully structured organics measurement, the Food Well Alliance’s presentation and workshop about applying design thinking to composting systems was a natural transition. Also based in Atlanta, the Food Well Alliance’s Will Sellers and Britni Burkhardsmeier walked meeting attendees through their unique process of using learning tables, working tables, and design tables that aim to facilitate collaboration between stakeholders and accelerate the process of precise interventions for a resilient food system.

In particular, Sellers and Burkhardsmeier shared the twists and turns throughout the evolution of the design and implementation of a composting pilot that intends to collect food scraps from multi-family buildings, diverting them to decentralized community-scale composting in the immediate local area. Keeping equity, resilience, and healthy food in the front of mind, this pilot is in an early stage of implementation and promises to be a fascinating and scalable case study.

In turn, the the Food Well Alliance’s intuitive inclusion of composting in a larger discussion about fresh food sparked a meaningful discussion about whether this strategy of nesting food waste composting within the broader context surrounding closed loop food systems could be effective on a large scale. With a majority of attendees in consensus that capitalizing on the momentum evident in sustainable food today, reframing food waste composting as one portion of this cycle, rather than a solid waste management strategy, could provide a more accessible engagement strategy to individuals, commercial entities, and governments widely.

Historically, we have associated resource consumption with the well being of a society. Prosperous economies and societies have needed to use more resources to continue growing. This link however has led to the development of wasteful practices in the global production and consumption of goods and services, with little regard for optimizing the use of materials or finite natural resources.

This poses a problem for society and the planet, as is evident in the rising importance of global environmental problems like marine plastic pollution, deforestation, and climate change. The UN’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) #12, Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns, challenges us to rethink linear make-take-waste models and provides an important call to action for business and consumers.

Should the global population reach 9.6 billion by 2050, the equivalent of almost three planets will be required to provide the natural resources needed to sustain current lifestyles. Population growth and a rapidly rising middle class in large economies like India and China demand that we future-proof our production systems to sufficiently allocate resources to meet growing demands in a way that does not continue to undermine the ecological systems on which we depend. There is need for improvement across all of our resource management systems.

Packaging plays an important role in society to protect products and reduce waste. For example, each year, an estimated one third of all food produced ends up rotting in the bins of consumers and retailers, or spoiling due to poor transportation and harvesting practices, a problem that packaging (and smart portioning) can help to prevent.

On the other hand, packaging represents a one-time use item that is quickly discarded upon reaching the consumer. While recycling rates for some packaging materials, like corrugated cardboard are high, recycling for many other materials remains unacceptably low – with a 26% recycling rate for other paper and paperboard packaging paper and 15% for plastic packaging in the U.S. China’s import ban on U.S. recyclables presents further risks that have the potential to erode the recycling system.

The energy used to create packaging is wasted when the package is sent to the landfill rather than recycled into a new package or another product, contributing to high embodied greenhouse gas emissions. Marine debris represents a new era of crisis in the pollution of our oceans, with studies citing plastic packaging as a top contributor. Governments are responding with new regulations requiring recycled content or banning certain materials all together.

SDG 12 provides a list of measurable targets to guide action by companies and governments by 2030. For example:

- Halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses;

- Achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their life cycle, in accordance with agreed international frameworks, and significantly reduce their release to air, water and soil in order to minimize their adverse impacts on human health and the environment;

- Substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse;

- Encourage companies, especially large and transnational companies, to adopt sustainable practices and to integrate sustainability information into their reporting cycle;

- Ensure that people everywhere have the relevant information and awareness for sustainable development and lifestyles in harmony with nature;

- Support developing countries to strengthen their scientific and technological capacity to move towards more sustainable patterns of consumption and production

These targets suggest some specific actions for business, and many companies have already started to conduct these activities and align their corporate sustainability goals. Evian, Coca Cola, Amcor and McDonald’s have just recently made ambitious public commitments to recyclability, recycled, and renewable content in packaging. Unilever has committed to projects to improve recycling in developing counties in an effort to combat ocean waste. Overall, attention is growing to the widespread use of hazardous chemicals in grease- and moisture-resistive barriers in packaging, and the growing number of companies with CSR reports demonstrate how sustainability reporting is becoming mainstream.

Indeed, packaging improvements and innovations offer significant power to contribute to achieving SDG 12 and its specific targets. Many of the solutions require new innovations in material design, recycling technologies and infrastructure, linking SDG 12 closely to SDG 9, “Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation.” Business plays a major role for meeting these two SDGs in particular.

Engaging companies on SDG 12 at SPC Impact 2018

This year at SPC Impact, we will discuss many aspects of SDG 12 and how companies can implement them.

Sustainable packaging starts with design and materials sourcing, and extends through transport and use phases by the consumer to the recycling of packaging materials that are then directed into end markets that close the material loop. The SPC Impact session: Knowledge Cafe: Sustainable Forest Products Sourcing will cover sustainable sourcing for forest products with McDonalds, Mars, Weyerhauser, Iggesund Paperboard, and Sappi. In Squaring the Circle: Balancing Source Reduction and Recyclability in a New Reusable Packaging Platform, Cleanyst will discuss their mission to reduce packaging waste and the carbon footprint in the design phase and use of home and body care products. The Least Sustainable Option with ISTA, will explore how to strike a balance between product protection and sustainability in the transport of products to consumers.

Thinking about material health impacts during the packaging use phase, Chemicals in Motion led by GreenBluewith speakers from Expera Specialty Solutions, San Francisco Department of the Environment, University of Notre Dame and Coop Denmark will discuss chemicals and health Implications in Food Packaging. At a package’s end of life, Evolving Flexible and Multi-material Packaging will discuss how we can resolve tradeoffs between food waste prevention or end-of-life on multi-materials in packaging with Printpack, Amcor, NOVA Chemicals, The Dow Chemical Company, and Recycle BC. Sessions are also dedicated to closing the loop in recycled material markets. In Creating End Markets for Recycled Materials, Klöckner Pentaplast defines the challenges and opportunities in end markets that will help enable use of recycled content for use in new products.

From responsible sourcing to source reduction to recyclability to recycled content, these conversations help to decouple economic growth from resource use, as businesses explore how they can boost their bottom line with improvements in material efficiency and a sustainable value proposition to customers.

It is in businesses’ interest to understand these issues and to find solutions that enable sustainable consumption and production patterns that ensure the security of their operations as well as their continued social license to operate.

The market for products formulated with safer chemistries is growing significantly.

There are many challenges for companies who want to develop safer alternatives. The first step is to successfully find safer substitutes for the chemicals of concern a manufacturer seeks to replace. Then there is performance testing to make sure that the finished product is as efficacious as its predecessor. Then, finally, a manufacturer has to find effective methods to market its improved products to existing and prospective customers. Within the household and institutional cleaning products sector, CleanGredients is one way ingredient suppliers can communicate third-party verification that their ingredients are safer for human health and the environment, but some companies take it a step further and highlight their CleanGredients listings in marketing and educational materials. These suppliers take on the role of educating their customer base about their innovations, and help product formulators find the resources they need to formulate safer products that their customers want.

Some suppliers that list in CleanGredients have made an effort to help their customers navigate EPA’s Safer Choice certification program. For example, late last year, Stepan Company released a product and formulation guide entitled “Navigating Safer Choice”, which makes it easy for customers who may not be familiar with CleanGredients and Safer Choice to understand which of Stepan’s home care ingredients are environmentally preferable options that meet Safer Choice criteria. The guide identifies how each of Stepan’s CleanGredients-listed products can be used in product formulations, as well as which of their products meet other green chemistry criteria, such as bio-based content. It also highlights Stepan’s starter formulations, which are formulations that can be used as-is for a variety of cleaning applications, or can be customized with a formulator’s colorant or fragrance, making it easy, especially for small formulators, to get a product with the Safer Choice certification to market. Stepan has supplemented their latest guide by supporting the Safer Choice program in other ways, such as participating in webinars designed to educate other stakeholders about the program. Their commitment to the Safer Choice program was acknowledged by EPA when they were recognized as a Safer Choice Partner of the Year in 2015 and 2017.

Other companies are also trying to educate their customers about ingredient options meeting the Safer Choice criteria – both for ingredients used in product categories eligible for the Safer Choice certification as well as for ingredients that meet Safer Choice master criteria and are considered to be safer alternatives to other options on the market. BASF Corporation uses the Safer Choice Standard and CleanGredients as two tools in its toolkit to clearly communicate which of its ingredients are safer alternatives and to help its customers make informed decisions. Within its Home Care and I&I Cleaning business unit, BASF’s CleanGredients Product Guide for Safer Choice Formulations identifies groups of ingredients meeting the Safer Choice standard and listed in CleanGredients, along with relevant applications in home care products and suggested formulations, making it easier for customers to formulate products that can achieve the Safer Choice certification. But BASF has also chosen to join Eastman Chemical in listing a non-ortho-phthalate plasticizer, Palatinol® DOTP, in CleanGredients. While this ingredient is not yet used in product categories eligible for the Safer Choice certification, because it is listed in CleanGredients, BASF can reassure its customers that it meets the Safer Choice Master Criteria and is a safer option for human health and the environment.

More and more chemical suppliers are recognizing that they have a key role to play in educating their customers and helping them select lower-hazard ingredients that will be used in end products that are safer for human health and the environment. Listing an ingredient that meets the Safer Choice criteria in the CleanGredients database provides important third-party assurance that it is a safer alternative, but suppliers have the opportunity to go further, leveraging their CleanGredients listings to help their customers understand their options and to ultimately create safer, more effective products their customers want.

GreenBlue is pleased to announce that Tristanne Davis has joined the team as a Project Manager with The Sustainable Packaging Coalition. Tristanne has a Master of Environmental Management from Yale University, an M.B.A. from the IE Business School, and a degree in Economics from Skidmore College.

GreenBlue is pleased to announce that Tristanne Davis has joined the team as a Project Manager with The Sustainable Packaging Coalition. Tristanne has a Master of Environmental Management from Yale University, an M.B.A. from the IE Business School, and a degree in Economics from Skidmore College.

Tell us about your background. Where did you spend your formative years and where did you go to school?

I grew up in a small town in New Jersey known for its art and antiques. My mother is an artist and I grew up thinking my future would also be in an artistic field. I went to pursue my Bachelor’s degree originally as a theater student, but after being exposed to the liberal arts world, I changed my focus to international studies, economics and the environment. I studied abroad in Tanzania, India, New Zealand and Mexico, and gained a strong interest in global development and environmental economics. I started my career in Washington D.C. as an environmental policy consultant and then moved on to work at a community development and food security-focused NGO in Nicaragua. I eventually returned to school to study environmental science and business, with a growing interest in the role that business can play to address environmental problems. I focused much of my studies at Yale around the circular economy for products and packaging and then moved to Spain to pursue my MBA after receiving a Fulbright grant.

What inspired you to work in the sustainability field?

I have seen many negative impacts that careless business practices and poor governance can have on the resources that we depend on, particularly in developing countries. Through my work and studies however, I have also been inspired by how effective policies and innovative companies can solve environmental problems and help push society in a more sustainable direction. In addition, I love the outdoors and have spent considerable time outside studying soils, trees, etc. and believe that nature has many lessons that society can learn from. I am motivated to be part of our evolution in this direction.

What do you hope to achieve at GreenBlue?

I hope to help GreenBlue spread knowledge of sustainable materials management and facilitate meaningful collaboration between business and government stakeholders. I want to add to GreenBlue’s efforts to work with its members and partners to develop innovative ideas, launch new partnerships, produce valuable information and tools, and advance the conversation around materials sustainability. I also hope to learn from the team and member community and have a lot of fun in the process!

What do you like to do in your spare time?

I have always loved learning about new cultures, both abroad and within the U.S., and try to travel as much as I can. I like to practice my Spanish by chatting with friends from Spain and Nicaragua and am currently working on learning Italian. I love gardening, cooking, and home craft projects, like making my own soap. I am looking forward to exploring the natural beauty of the Shenandoah Valley area.

Happiness is…

Learning something new! A new recipe, a new concept, a new art medium, exploring a new place. In general, I find happiness when being surrounded by plants, animals, and interesting people.

Welcome Introduction: Alisha Dakon

GreenBlue is pleased to announce Alisha Dakon has joined the team as the Information Systems Associate. Alisha has a degree in journalism and is currently pursuing her Master of Arts in Educational Technology Leadership from George Washington University.

Tell us about your background. Where did you spend your formative years and where did you go to school?

I grew up in Charlotte, North Carolina and, for as long as I can remember, I wanted to be a teacher. I endeavored after this goal by enrolling in the music education program at Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina on violin and piano (where I also learned to play the tenor steel drum). Out of curiosity, I joined ASU’s student newspaper and unexpectedly became passionate about journalism. I soon discovered I was captivated by the variety, stories, photography, graphic design, and creative freedoms of the communications field. Eventually, I changed majors and graduated from ASU in 2009 with a Bachelor of Science in Communication, Journalism with a minor in music. After graduating, I moved to Roanoke, Virginia with my husband where we later welcomed our imaginative, spunky, and loving daughter who has rounded out our happy family of three. While living in Roanoke, I was employed at a law firm for five years and then a healthcare provider for two years. In January 2017, I was accepted into the online program for a Master of Arts in Education and Human Development in Education Technology Leadership at George Washington University to focus on instructional design and e-learning. In the summer of 2017, we took a leap and moved to Charlottesville, Virginia for my husband’s job. It has been an easy transition and we absolutely love exploring this new place we call home!

What inspired you to work in the sustainability field?

As with law and healthcare, I do not have any formal background in the area of sustainability but find it fascinating and I am excited to learn more! As a typical consumer, I want to do my part to be responsible and help our environment so future generations, like my daughter, are not burdened with the disregard of how human actions impact our planet. I feel joining GreenBlue is the perfect opportunity to educate myself so I can also set a good example for others.

What do you hope to achieve at GreenBlue?

I hope to support the GreenBlue mission by blazing new trails! In particular, I am thrilled to discover how intensely GreenBlue encourages innovation and collaboration to inspire effective change in the field of sustainability. Specifically, I look forward to building pathways and products that facilitate the sharing of information, implementing emerging technologies to push the envelope of the status quo, and finding ways to make system processes both more efficient and productive so we have more time to do great work. It is an awesome adventure to be a part of!

What do you like to do in your spare time?

I enjoy spending most of my spare time with my husband and daughter. Since moving to Charlottesville, our family has joined a karate studio and we are each dedicated to earning our black belt at the end of our anticipated three-year journey. After family, I spend a lot of time drinking coffee while studying, exploring, and researching for my graduate degree. As we settle into our new surroundings, we look forward to learning more about Charlottesville and how we can give back to this great community!

Happiness is…

Playing with my daughter and making her laugh is happiness in a nutshell! After that, my personal philosophy for happiness embodies a quote by Albert Einstein, who said, “I have no special talents. I am only naturally curious.” I definitely look forward to each new day as a chance to openly acknowledge there is so much I don’t know and how very exciting it is to wake up in anticipation of all there is to learn. Last but not least, I also hope for the opportunity to help someone else and it’s an added bonus if I can apply what I’ve learned while doing so!

Companies wishing to thrive in the Fourth Industrial Revolution should adapt their packaging systems and strategies to today’s changing circumstances.

In “How the 4th Industrial Revolution will impact packaging, part 1,” we explain how production systems are changing as consumer consumption trends shift. Because packaging touches all products, packaging will also fundamentally change.

Here are seven ideas on how you can adjust to what might well be the new normal.

1. Reconsider the context and friction of your packaging.

As packaging designers reconsider their product/packaging system in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, it will be critical to analyze the evolving context and friction of packaging. In this sense, the context of packaging refers to the situation the packaging finds itself in throughout its life.

One example of how the context of packaging is changing is how people are dissembling a shipping carton or pouch in their living room instead of taking only the primary packaging home from the store. One should ask questions like, how do packaging needs change if they don’t need to always be scanned as individual units at a checkout and then be brought home in the trunk?

In turn, the friction of your packaging could refer to the burdens (could be clerical or emotional burdens) that your packaging puts on the consumer or the fulfilment process. For example, how does the friction of unpacking a product impact a consumer’s impression of your brand if the corrugate that used to be invisible, baled up back of house at their local store, is now quite visible to the consumer, needing to be broken down and stuffed into an overflowing curbside recycling bin? What if you’re placing unnecessary friction on the consumer by over-packaging because you’re paranoid about damage, and it ends up damaging your brand equity instead?

For these reasons, one consideration the consumer packaged goods (CPG) industry should think seriously about―for long-term brand equity―is investing in curbside recycling infrastructure. If our voice assistant is going to bring our favorite shampoo right to our doorstep in a matter of hours, but we don’t have a smart recycling bin connected to a crazy underground waste network that turns it into another shampoo package, have we really reached the future, or are we creating debt? Non-recoverable packaging, packaging that isn’t sustainably sourced or excess packaging will all look painfully old-fashioned alongside things like artificial intelligence and self-driving cars.

2. Note how Amazon is disrupting the new context and friction of packaging.

Amazon is somewhat radical because it is prominently focusing on tackling what it deems the new “branding shift that is driving a different first moment of truth for customers.” By zeroing in on how people are perceiving and experiencing packaging through ecommerce, Amazon is in many ways facilitating a new era of packaging sustainability. That’s because it’s viewing packaging sustainability more through the eyes of the people, and less through the eyes of the business.

Probably as a direct result of Amazon’s self-identified “obsession” with the customer (which it believes is much different than being competition-focused, technology-focused or business model-focused), it has created the Frustration-Free Packagingcertification. This certification notably requires all packaging materials must be curbside recyclable and designed to reduce waste.

While many brands look to sustainable packaging from the outlook of helping the business save money (for example, by using less materials) or to manage risk (such as moving away from finite materials in a changing climate), Amazon is looking to sustainable packaging so that consumers don’t personally experience frustration. This shift in perspective conveys an implicit understanding of the changing context and friction of packaging. It is also a refreshing example of a company taking responsibility for its own packaging by giving consumers the benefit of the doubt, and removing a burden from their shoulders that was arguably not even theirs to begin with.

3. Embrace collaboration.

Another way to thrive in the Fourth Industrial Revolution is by embracing collaboration, which improves connectivity and learning. You can respond faster to change when you’re not in a bubble―and you’re exposed to more helpful information and perspectives, too. Locking yourself away at your headquarters and guarding every aspect of your business like you’re Willy Wonka―that’s not very 2017.

Look to NGOs (non-governmental organizations) to cut through the noise in packaging sustainability in these evolving circumstances, such as the Sustainable Packaging Coalition. The supply chain is rife with various sustainability claims, and many of those claims in emerging sales channels are misleading. Instead of taking each supplier at its word about the recyclability of packaging, brands could collaborate with How2Recycleto get impartial information about their packaging that they can trust.

Companies can also collaborate with each other along the supply chain to unlock new opportunities. For example, Amazon collaborates with brands to optimize packaging design for ecommerce by being transparent across product portfolios about packaging performance data, and by identifying key opportunity areas to drive sustainable packaging solutions.

4. Invest in data acquisition and analysis.

Big Data is part of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and it will help packaging adapt and succeed, if companies are serious about getting it and interpreting it properly.

Specifically, packaging damage data will be an essential driver as goods will be moved in such different, dynamic ways than before. Advanced analytics about the supply chain will help companies make their packaging designs more responsive and efficient, and will facilitate transparency about the sourcing and production of packaging materials.

5. Minimize distractions.

There’s a temptation when we dream about and fear an unknowable future to jump to solutions that look like they’re out of The Jetsons out of a desire to dazzle or leapfrog. Many in the packaging world tend to be drawn to the “hottest” new innovations or materials that sound more sustainable but actually may clash with our existing recovery infrastructure. For example, you may not want to slap geolocation hardware onto packaging until, and unless, you can demonstrate that it’s designed for recyclability (and not just begrudgingly tolerated by some recyclers in small quantities).

In other words, don’t just follow shiny things.

6. Equip packaging and sustainability professionals with the right skills and information.

Another variable that will contribute to the natural selection of packaging in the Fourth Industrial Revolution will be skills. Too many packaging professionals―or sustainability professionals―don’t know the fundamentals of packaging sustainability or have a starting point to begin managing tradeoffs.

Courses like the Essentials of Sustainable Packaging and attending events like SPC Advance can help, but companies should make more of an overall investment in sustainability education and talent if we hope to have workforces that understand what life-cycle assessments are and can do, and also have the ability to contextualize and interpret those assessments within the greater product, packaging and logistics systems.

Another skill that isn’t mentioned enough in sustainability is persuasion. If you’re the champion of sustainability and change within your organization and you haven’t got the people above and around you bought into what you’re trying to do, your progress will be limited in these accelerating times. Collecting, curating and interpreting the information available to you, and being able to express and share that in a way that’s meaningful and compelling, will be a true differentiator.

7. Change attitudes and the way decisions get made.

Finally, attitude is going to be key in leveraging packaging opportunities in this revolution. I’ve written before about how sustainability is change, and change is painful; but as we can learn from the natural world, there is no greater threat to survival than resistance to adaptation or inability to adapt.

Part of what this might mean for brand leaders and packaging professionals is to be genuinely open to disruption. As Jeff Bezos explained in his 2017 letter to shareholders, “If you fight [powerful trends], you’re probably fighting the future. Embrace them and you have a tailwind.” The Economist echoed this sentiment recently when it warned(actually in reference to Amazon’s “competitive rivals”): “Settle for mediocrity at [your] peril.”

Attitude is directly linked to how companies make decisions. Decision-making qualities recognized as critical to adaptation in this shifting business world are the ability to be agile and the willingness to act and take risks. In the words of Elon Musk, “If you aren’t failing, you’re aren’t innovating enough.”

I have spoken with people at companies who openly concede they won’t make their packaging more sustainable unless and until their direct national brand competitors are doing so in a way that threatens their sales. Or another company said they’d use the How2Recycle label only if one of their big retail customers literally forced them. So let there be no confusion that there are entire packaging strategies out there built only on begrudgingly following others or the threat of a stick.

While a recent poll found that a little more than a third of retail companies areinvesting in reconfigured fulfillment infrastructure for ecommerce within the next three to five years, “‘organizational inertia” is still the number one obstacle in companies investing in the most important factors driving their business. This reminds me of how Anna Wintour, editor-in-chief of Vogue, reflects on the growing pains she’s observed in recent years as the internet permanently altered journalism:

“One overwhelming message, particularly from Silicon Valley, is that you can’t be frightened of change. A traditional company is the most difficult to pivot and you have to be open to new ideas and not be worried about failure. I think when things are challenging and different, it’s actually also a very exciting time, because it does give you a freedom to try different things…. [Y]ou get a little insular and caught up in your own world and doing things a little bit too much the same way…. This is the problem of very long established companies…. I’ll be the first to admit that at Condé Nast we have been guilty of arrogance—we are Condé Nast, we have always done it this way. We are so busy working at being the best, being perfect, that we haven’t always been open to disruption. I hope that’s changing.”

Wintour has succeeded at maintaining the relevance and popularity of Vogue amongst significant shifts in the fashion and media industries because she recognizes that clothing is a reflection of who people are and the times we live in. As things change, she believes, so should Vogue. Similar to clothing that a person chooses to wear, packaging is a telling expression of a company’s self―that can serve as a mirror of that company’s values.

Who will you be?

“[Do you] wanna embrace your destiny, or [do you] wanna get by[?]” ―Rick Ross, “Nobody”

This article was originally published in Packaging Digest

Sustainable packaging strategies will need to adapt to the massive restructuring of the retail industry, a shifting global logistics infrastructure and a changing notion of consumption itself. Kelly Cramer zooms out—way out—to explain why and how industry can reconsider packaging for the next era of production.

The world is changing as we enter the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

You don’t have to look far in the media, or even within your own immediate surroundings, to see that the world is changing by grand leaps―and with haste. Some, such as those at the World Economic Forum, are characterizing the many changes seen in the last few years as the Fourth Industrial Revolution (aka Industry 4.0). Building upon the Third Industrial Revolution of the internet and automation (that is still ongoing), the Fourth Industrial Revolution is marked by advancements that fuse the physical with the digital. Robotics, the Internet of Things (IoT), 3D printing, advanced materials and artificial intelligence are all examples of this. Every industry will be disrupted with a velocity, scope and systems impact that has never been seen before.

Due in part to changing behaviors and desires, consumption is changing.

Among the areas that will be change by this revolution, and that is already changing before our eyes, is the notion of consumption itself. What people are consuming, how and when they’re consuming it, and where the consumption takes place is changingquickly. The astronomical rise of ecommerce is the most obvious aspect of changing consumption, but there are other compelling changes, including the explosion of subscription products, the success of brands with super-fast production cycles and the growth of the sharing economy.

As a result of these new sales channels and an evolving consumer experience, we’re observing greater customization of products, better accessibility to products, the prioritization of convenience, and more engagement between consumers and brands.

As consumption is changing, the systems of production are also changing.

Due at least in part to these changes in consumption, we’re observing a fundamental restructuring of the retail industry that is in process right now. What’s happening right now isn’t just “American malls have too much real estate vacancy.” Anyone who sells anything―not just the apparel companies or department stores in headlines―will be impacted by the consumption evolution. The idea of what a store is may change considerably in the coming years as shopping becomes more digitized and multidimensional. Like journalism before it, the consumer packaged goods (CPG) industry will likely get “leaner and meaner.”

The shift in the sale of goods to new channels and consumption habits is very much related to the global shift in logistics. The way things move through our world is being optimized, automated and reshuffled. Additionally, manufacturing and supply chainsare becoming smarter, more agile and interconnected.

Sustainability is a new standard and expectation in production and consumption.

In addition to systems changing, circular economy and sustainability have become key considerations in the modern business model. The rise of the aspirational consumer (who places high value on environmental responsibility), combined with the disproportionate and unprecedented buying power of the millennial generation (that loves sustainability), means that every day you’re not investing in sustainability you’re losing much longer time down the road to catch up. If you’re able.

Because packaging touches all products, and because consumption and production are fundamentally changing, packaging will also fundamentally change.

Packaging is connected to the sale of all products; it is the common material thread between all things sold. Packaging must first and foremost protect the product. If packaging fails and the product gets damaged, you lose the entire capital, environmental and human investment that went into making that product. Often, the “footprint” of packaging is much less than the actual product itself.

For this reason, studying how the packaging relates to and interacts with the product―or in other words, analyzing “the product/packaging system”―is essential to creating sustainable packaging. A package is well-designed so long as the amount of material used in packaging is enough to protect the product but no more.

The role of packaging in the ecommerce channel enables something much differentfrom packaging than traditional retail does. This past spring at the Sustainable Packaging Coalition’s conference SustPack, Dr. Kim Houchens and Brent Nelson of the Amazon packaging sustainability team explained how products that move through Amazon fulfillment are handled on average 20 times, versus the minimum of five for brick-and-mortar retail. And while the product isn’t handled individually until it reaches the shelf at a brick-and-mortar store, in Amazon fulfillment centers, pallets are broken down into individual units much earlier in the process, and re-aggregated into shipping packages for each unique customer order. And because packaging doesn’t move with a certain side facing up in ecommerce, it means that certain fragile products like liquids sometimes need to be packaged differently to prevent leakage. This shows that you’re hiring packaging to do a very different job in ecommerce than you are for traditional retail.

The traditional product/packaging system will struggle in the Fourth Industrial Revolution if it doesn’t adapt fast enough to the new demands put on it―but these changes can also set packaging free.

One way that the traditional product/packaging system is falling short in ecommerce is in product damage rates. Amazon is encouraging its vendors to think seriously about avoiding product damage, because it creates a terrible customer experience. Specifically, the etailer has worked with ISTA to develop a test to simulate how packaging moves throughout the Amazon fulfillment process. It includes two hours of vibration, 17 simulated edge corner face drops and a leak integrity test.

Amazon has also developed the Frustration-Free Packaging program to encourage brands to package product in a way that doesn’t require an Amazon box, and can be sent direct to the consumer without being repackaged in the fulfilment centers, potentially helping mitigate damage and also helping save materials.

One could argue that traditional retail in some ways holds sustainable packaging back―because of prevailing marketing conventions. Brands want shelf presence, which may mean excess materials to “increase real estate” and flashy labels or inks that could negatively impact recyclability. But as Amazon has emphasized, expensive “romance” packaging isn’t required to draw the consumer’s attention in ecommerce; it’s the product, not the packaging, that is displayed to consumers online when they buy, so the consumer doesn’t need to touch or feel the packaging to make a purchase decision (packaging functionality, however, is still critical for the consumers’ usage experience). Additionally, the need of theft protection no longer being relevant will also help companies use fewer materials.

Another significant challenge to the traditional product/packaging system is the newer dimensional weight pricing rules from the big carriers like UPS and FedEx that will make it significantly more expensive to ship larger volume packaging (air, that is) direct to the consumer. Changing logistics costs will add complexity to the product/packaging system, but overcoming these challenges will provide significant carbon benefits. In this sense, packaging sustainability will be more tied to logistics sustainability than before.

Another interesting possibility is when and if the need for more sustainable packaging and the cost of logistics ends up changing the products themselves. One classic example is movement toward concentrates to avoid shipping water, but we’re seeing flashes of an exciting new horizon with Amazon’s plunge into microwave assisted thermal sterilization (MATS). We may not need into ship ice packs if, in the future, we’re eating more food that doesn’t require refrigeration. Packaging will be at the forefront as processing technologies, changes to the products themselves and the tightening of logistics efficiencies dramatically reconfigure the product/packaging/process system.

Part 2 of this series will examine what industry can do about adapting packaging for this next era of production.

Last month, four paint companies settled Federal Trade Commission charges that they made deceptive environmental claims, without adequate evidence to back up the claims. Among other things, the companies’ unqualified claims that their products were emission-free, VOC-free, and safe for sensitive populations got them into hot water with regulators. Paint companies are not the only ones falling into this trap. In the past, cleaning and personal care product companies have also come under fire and been subject to lawsuits for claiming that their products are natural, non-toxic, or safer than their competitor’s products.

This serves as an important reminder that, even as more and more consumers are looking for products that make “green” claims, brands need to be careful and avoid making vague assertions about their products that aren’t backed up by clear evidence. The FTC’s Green Guides provide guidance to companies to help ensure they don’t make claims that will be misinterpreted by consumers. For example, companies shouldn’t make broad, unqualified environmental claims, such as their product is “green” or “eco-friendly., They should also disclose any connections with certifying organizations if certifications or seals are used, so consumers don’t misinterpret a company’s own seals of approval as third-party certifications. So how can companies ensure that the environmental claims they make are backed up by evidence?

Third-party certifications like EPA’s Safer Choice can be incredibly valuable to companies that want to market their products based on environmental and health attributes. Participating in the Safer Choice program allows products that meet the standard to use the Safer Choice label on their package and marketing materials, indicating that the product contains ingredients safer for human and environmental health than conventional products. Every ingredient in a Safer Choice-certified product must meet EPA’s rigorous science-based criteria, and all products undergo review by independent toxicologists before they can carry the label.

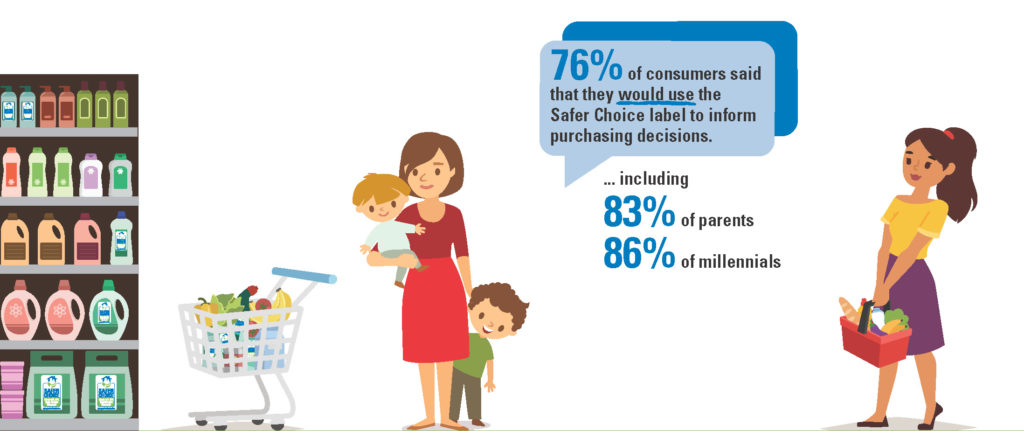

Companies marketing Safer Choice-certified products find that the label is both meaningful to consumers, helping companies market their products to those looking for “green” options, and scientifically meaningful, so it stands up to scrutiny. An EPA study in February 2016 found that more than a third of consumers were familiar with the Safer Choice program and had seen the label on store shelves. After learning about the certification, more than three quarters said that the Safer Choice certification would inform their future purchasing decisions.

The market for safer products is substantial. In fact, a Consumer Reports surveyfound that 44% of the American adults surveyed would pay more for cleaning products they perceive to be safer for their health and the environment. Third-party certifications like Safer Choice can help companies access this market, without falling into the trap of making vague and unsubstantiated claims that could land them in legal trouble. Plus, consumers who see the Safer Choice label on a product will know that the claims are backed up by rigorous, independent review, so they are actually getting the safer, more environmentally friendly products they want.

Packaging is a discipline that evolves constantly and few aspects of packaging are changing as quickly as bioplastics. The speed of change in the bioplastics space is cause for some of the confusion that often surrounds the topic. But a lot of misunderstanding is simply due to the fact that it’s an incredibly heterogeneous space.

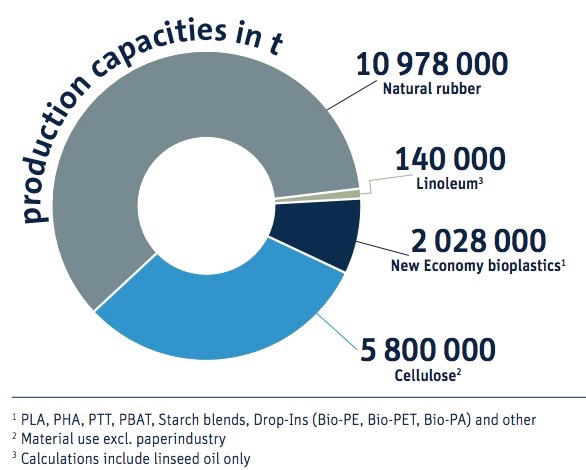

At first glance, the bioplastics category can seem incongruous, containing materials that are either biobased or biodegradable, or both. This translates to novel chemicals like PHA, “drop-ins” like bio-PET that are recyclable, and “old economy” bioplastics like rubber, gelatin, cellulose, and linoleum that were introduced before the availability of petrochemicals. Today, these old economy materials make up 17 million tons of the total 18.9 million tons of global bioplastics production capacity.

Though a minority of the current market, the production capacity of new economy bioplastics has increased consistently, clocking in at approximately 15% annually from 2013 to 2016. The subset of new economy materials consists primarily of either drop-in bioplastics that have chemically identical structures to conventional plastics like PET or PE, as well as new formulations like PLA or PHA that have chemical structures unrelated to conventional plastics.

Appropriately, many drop-in bioplastics that mirror conventional plastics can be recycled just like their petrochemical counterparts. A PET bottle made of petroleum is recyclable, and so is a PET bottle derived from sugarcane, corn, or potato starch. A PET bottle that contains a mix of petroleum and plant-based feedstocks, like the Dasani and Coca-Cola PlantBottle that includes 30% bioplastic content is also just as recyclable (with cap on, please). Just like conventional plastic packaging too, bioplastic packaging can have a recyclable base material, like bio-PE, but be made unrecyclable through problematic adhesives, coatings, barrier layers, and colorants, among other factors.

Appropriately, many drop-in bioplastics that mirror conventional plastics can be recycled just like their petrochemical counterparts. A PET bottle made of petroleum is recyclable, and so is a PET bottle derived from sugarcane, corn, or potato starch. A PET bottle that contains a mix of petroleum and plant-based feedstocks, like the Dasani and Coca-Cola PlantBottle that includes 30% bioplastic content is also just as recyclable (with cap on, please). Just like conventional plastic packaging too, bioplastic packaging can have a recyclable base material, like bio-PE, but be made unrecyclable through problematic adhesives, coatings, barrier layers, and colorants, among other factors.

Some bioplastics that are biodegradable are also biobased and derived from plants. PLA, for example, is fit for composting at industrial composting facilities and is created either by fermenting sugarcane or sugar beets or through the hydrolysis of wheat, potato, corn, or other starches. Other biodegradable plastics are not bio-based, like BASF’s ecoflex®, a PBAT polymer that is industrially compostable and made from adipic acid and butanediol.

Often, choosing a plant feedstock for a bio-based plastic, whether biodegradable or not, is predicated on geography. In some regions, feedstocks like corn are abundant and cheap. In others, sugar beets are plentiful. Corn starch is the primary feedstock for PLA in North America, cassava is used most in Asia, and sugarcane throughout South and Central America. NatureWorks, for example, sources the corn used to create its Ingeo PLA polymer from the 300 miles surrounding its Blair, Nebraska facility.

Apart from availability, other considerations like water and land requirements to produce one ton of a given feedstock are important, as is the tons of feedstock required to produce one ton of bioplastic. To produce bio-PE, for instance, sugar beets require 5 times less water and a 6 times smaller land footprint than wheat per ton of feedstock. On the other hand, only 10.86 tons of wheat are needed to produce 1 ton of bio-PE while 27.25 tons of sugar beets are necessary to produce the same quantity.

Besides the feedstocks most commonly used to produce bio-based plastics today, a slew of lignocellulosics like bagasse, wood chips, straw, and switch grass are undergoing more research and development and are starting to penetrate the market. Futamura’s NatureFlex™, for one, is a bio-based compostable film made from wood pulp at managed plantations, including FSC-certified forests. Nevertheless, Erin Simon of the Bioplastic Feedstock Alliance explains that as the new economy bioplastics industry continues to grow, “All feedstocks will have advantages and disadvantages, so the focus should be on committing to the continuous improvement of the best available feedstock option for that technology and sourcing region.”

Today, the portion of new economy biobased production currently exceeds that of biodegradable plastics. The ratio has magnified in recent years, and projections strongly suggest that this chasm will increase considerably towards 2020 and beyond. The Institute for Bioplastics and Biocomposites’ 2016 report quantifies that in 2015, 37% of new economy bioplastics were biodegradable and 63% were biobased, but non-biodegradable. By 2020, however, biodegradable plastics will represent 18% of bioplastics production and bio-based, non-biodegradable plastics will rise to 82%.

This is not to say that because biodegradable plastics will make up a decreasing percent of all new economy plastics production that the production itself is decreasing. From 2015 to 2020, biodegradable plastics will see an estimated annual growth rate of 25%. Over these 5 years, biodegradable plastics use in non-packaging applications are expected to increase in textiles, agriculture and horticulture, as well as the automotive and transport sectors.

In a few categories, the dominance of biodegradable plastics and non-biodegradable, bio-based plastics will flip. Consumer goods, for one, is majority sourcing from bio-PET and other bio-based plastics, but by 2020 is expected to invert and be very heavily oriented towards PLA and starch blends. In contrast, the majority of bioplastics used in the automotive and transport sectors in 2015 are a cocktail of PLA, starch blends, and various other biodegradable plastics. Within 5 years, bio-PET and bio-PE will be used almost exclusively within bioplastic applications to this sector.

In a few categories, the dominance of biodegradable plastics and non-biodegradable, bio-based plastics will flip. Consumer goods, for one, is majority sourcing from bio-PET and other bio-based plastics, but by 2020 is expected to invert and be very heavily oriented towards PLA and starch blends. In contrast, the majority of bioplastics used in the automotive and transport sectors in 2015 are a cocktail of PLA, starch blends, and various other biodegradable plastics. Within 5 years, bio-PET and bio-PE will be used almost exclusively within bioplastic applications to this sector.

Overall, however, the majority of bioplastics production capacity will be in packaging. Flexible packaging and films in particular will experience a two-fold increase from 400,000 tons in 2015 to 814,000 tons in 2020. Yet, the majority of development will take place in the rigid packaging space where the 1 million ton production in 2015 will increase nearly 7 times to a whopping 6,897,000 tons by 2020. This non-biodegradable, but bio-based plastic will be mostly bio-PET 30, or PET rigid plastic with 30% bio-based content. Within the rigid packaging bioplastic growth, biodegradable plastics will increase from less than 200,000 tons of production capacity in 2015 to more than 1 million in 2020.

The industry production expansion makes sense when examining the corporate goals of large multinational companies and new government policies. France became the first country to ban single-use food serviceware made of conventional plastics in 2016. Starting in 2020, all single-use food serviceware will not only be required to be compostable, but home compostable, spurring new research and development for compostable plastics capable of biodegrading at lower temperatures typical to smaller residential-scale piles. This alone will drive many billions more units of compostable bioplastic items to the market and will be significantly augmented by new Italian legislation that mandates a similar home compostable serviceware requirement.

Large multinationals in the consumer-packaged goods space and elsewhere have also made progress or declared intentions to dramatically scale bioplastic use. Coca-Cola, already one of the biggest purchasers of bioplastics, has scaled bio-PET content to 30% in their PlantBottle. The company aims to continue increasing bio-PET content across more than 30 of their global brands.

PepsiCo has also made commitments to using biobased plastics in packaging. Vice President Roberta Barbieri strikes a similar note, explaining that because of the “tremendous greenhouse gas reduction benefit from bio-resins… A move to bio-based PET for our PET bottles would be a hugely impactful GHG reducing effort.” This strategy would roll up into PepsiCo’s Performance With Purpose goals, one of which is to “reduce greenhouse gas emissions across our entire value chain… by 20 percent in absolute terms by 2030.” Similarly, PepsiCo is doubling down on compostable films for its snack food packaging applications with many active pilots around the world and significant investment in Danimer Scientific to co-develop biodegradable PHA film, produced by microbial bacteria fermenting organically sourced oil. As a whole, PepsiCo has committed to distributing entirely recoverable or recyclable packaging by 2025.

Exploration certainly isn’t halting here, however, and investment in methods of transforming carbon dioxide into lactic acid, as well as methane into lactic acid, is underway. Producers of PLA are developing technologies to facilitate this process with the aim of turning greenhouse gases into compostable polymers, pushing New Economy bioplastics to new heights. Other research efforts are underway to convert materials like blood meal and feathers in addition to other animal waste products at the University of Waikato in New Zealand. Though plant proteins have long been converted to plastics, animal proteins have typically clogged extruders, University of Waikato chemical engineer Dr. Johan Verbeek discloses that “The process we’ve developed gets around that problem.” In the Netherlands, Wagenigen University researchers are forging bioplastic produced from seaweed, exploring ways that Europe can increase sustainable aquaculture where the region is only currently responsible for 0.5% of the 20 million tons of seaweed farmed globally each year.

Investigating other unconventional feedstocks, the Spanish company Ainia Technology has spent 4 years developing compostable PHB derived from the wastewater of fruit juice producers. Dr Ana Valera, associated with the Ainia project, shares that “The juice industry generates a lot of wastewater streams: for cleaning the fruit in different points, for cleaning the equipments used for manufacturing the juice, etc.” But, of the many options, the stream with the highest load of sugars, “was one from the cleaning process after the juice manufacturing.” While not yet tested in a pilot plant, the project represents an enticing plan to introduce food waste back into the economy as a circular material.

While mostly in beta phases, this incredible diversity of R&D in new feedstocks, particularly feedstocks like waste and emissions, reflect a strong commitment to getting materials that are currently escaping the circular economy back into a loop. The excitement that this generates is understandable. Yet, it should not eclipse parallel measures for packaging producers and brand owners to make space in their portfolios for recycled content.

Similarly, it’s critical to ensure that even when using a bioplastic that no confounding colorants, inks, labels, adhesives, fillers, barrier layers, or other amendments are made that compromises the recyclability or compostability of the package. And, as new economy bioplastic production increases year by year, the industry must make renewed efforts to communicate clearly to consumers.

The rising tide of bioplastics as a whole underscores unique ways to sequester carbon, transition from petroleum-based plastics, and create new products from waste. So, as research and production expansion occurs, the frenetic growth of bioplastics must also be tempered with reinvigorated communication to consumers about end of life, as well as renewed emphasis on sustainable sourcing as bioplastic feedstocks become more varied and logistically intensive. In all likelihood, responsible application of bioplastics in packaging and elsewhere will continue to lower cost and increase efficiency of production, catalyzing the transition to fossil-free packaging.