Edible packaging is hardly a new phenomenon. Experts estimate that natural sausage casings have been in use for at least 6,000 years and soy film known as yuba has been used as packaging in East Asia since the 16th century. Edible packaging has even been hiding under the noses of modern consumers for years in the form of pharmaceutical capsules made of gelatin or sugar.

In recent years, however, the diversity of edible packaging options has exploded. Packaging designers are now experimenting with materials like potato starch, beeswax, algae, and calcium, to name a few. Some of these materials offer potentially valuable attributes like extending shelf life or providing a vehicle for additives like nutrients, probiotics, and flavorings.

For instance, U.S. Department of Agriculture researchers just announced on August 22nd that a newly developed film made from the milk protein casein promises an oxygen barrier that is 500 times more effective than low-density polyethylene. Lead researcher Peggy Tomasula explains that this is a major opportunity as the casein film “could prevent food waste during distribution along the food chain.”

Another edible invention capable of having an equally disruptive affect on food waste is the MIT’s LiquiGlide. LiquiGlide is an edible gel-like coating that can be applied to the inside of glass, plastic, or aluminum containers and allows the product to slide out easier due to it’s “hyper slippery” quality. Though its abilities are often demonstrated in condiment bottles, the coating has many non-food applications for packaging items like toothpaste, paint, and glue.

Packaging innovations like LiquiGlide coating and casein film have been identified by ReFed as one of the three most effective strategies of 27 considered to reduce food waste nationwide. Consumer Reports estimates that LiquiGlide has the potential to circumvent the 3-15% of food waste generated when mayonnaise, or say, mustard, is stuck in a bottle. And, as the USDA estimates that Americans waste 30-40% of our food supply, that could quickly add up to a lot of diversion.

Though a majority of edible packaging is certainly intended to be eaten, like Brazilian burger chain Bob’s that offers burgers wrapped in edible paper, or WikiCells, which are soft foods like yogurt or ice cream directly coated in a hard, fruit-derived electrostatic gel, some are not. For example, Swedish design studio Tomorrow Machine designs beeswax pyramids that can be peeled like a fruit. While the beeswax is edible, it is unlikely that consumers would really want to chow down on it.

Importantly, to be sold commercially, anything edible needs to be contained in a non-edible package for the purposes of packing, transportation, and distribution. This stipulation of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act effectively removes any possibility that edible packaging will encroach on the market share of conventional packaging in the near future.

The main benefit of edible packaging revolves around its capacity to be an alternative to traditional primary packaging like plastic film that have recycling rates in the single digits. MonoSol, for example, has expanded its product line of water-soluble packets from laundry detergent pods to food items like oatmeal, where consumers can toss pre-measured oatmeal packets directly into boiling water where the edible film dissolves. The edible nature of the film allows packaging designers to play with flavoring possibilities like cinnamon or brown sugar and also reveals further potential for products like instant coffee, hot chocolate, or cooking oils.

One might expect companies that offer food items like instant noodles, baking kits, or flavor packets in rice dishes to adopt the  use of edible, water-soluble film as it already aligns with their touchstone concept of convenience. Likewise, makers of other food products like meal replacement shakes or protein powders that could benefit from pre-measured portions may foreshadow other early adopters of edible packaging like MonoSol’s film.

use of edible, water-soluble film as it already aligns with their touchstone concept of convenience. Likewise, makers of other food products like meal replacement shakes or protein powders that could benefit from pre-measured portions may foreshadow other early adopters of edible packaging like MonoSol’s film.

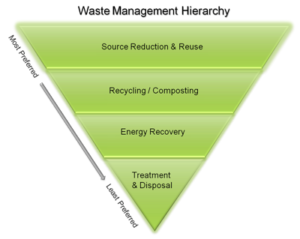

The multitude of materials evolving in the edible packaging space are reason to be excited, especially those that offer alternatives to packaging that are not designed for recyclability. But, managing expectations about bringing edible packaging to scale is critical and even edible packaging’s application for composting will be constrained by the growing, but sparse presence of composting facilities in the United States. Approaching the realm of edible packaging with cautious optimism as more varieties are piloted on a commercial scale will at the very least expand the toolbox of materials available to packaging designers. At best, it may eventually prove to be an important step towards closed loop sustainable materials management.

This spring, Caroline Cox joins the GreenBlue team as a project associate focused on the How2Recycle program. Caroline comes to GreenBlue from the Hampton Roads, VA area. Learn more about Caroline in the interview below.

This spring, Caroline Cox joins the GreenBlue team as a project associate focused on the How2Recycle program. Caroline comes to GreenBlue from the Hampton Roads, VA area. Learn more about Caroline in the interview below.