Packaging is a discipline that evolves constantly and few aspects of packaging are changing as quickly as bioplastics. The speed of change in the bioplastics space is cause for some of the confusion that often surrounds the topic. But a lot of misunderstanding is simply due to the fact that it’s an incredibly heterogeneous space.

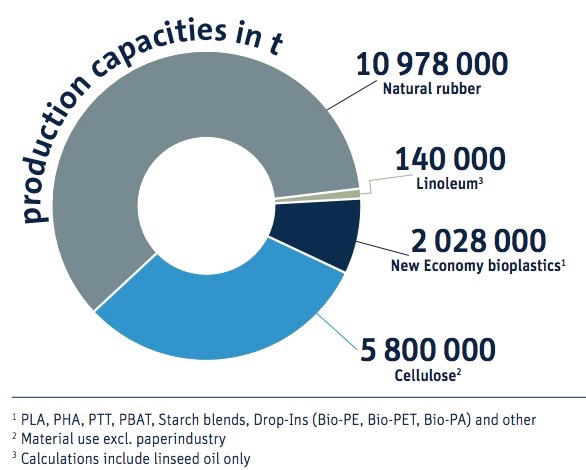

At first glance, the bioplastics category can seem incongruous, containing materials that are either biobased or biodegradable, or both. This translates to novel chemicals like PHA, “drop-ins” like bio-PET that are recyclable, and “old economy” bioplastics like rubber, gelatin, cellulose, and linoleum that were introduced before the availability of petrochemicals. Today, these old economy materials make up 17 million tons of the total 18.9 million tons of global bioplastics production capacity.

Though a minority of the current market, the production capacity of new economy bioplastics has increased consistently, clocking in at approximately 15% annually from 2013 to 2016. The subset of new economy materials consists primarily of either drop-in bioplastics that have chemically identical structures to conventional plastics like PET or PE, as well as new formulations like PLA or PHA that have chemical structures unrelated to conventional plastics.

Appropriately, many drop-in bioplastics that mirror conventional plastics can be recycled just like their petrochemical counterparts. A PET bottle made of petroleum is recyclable, and so is a PET bottle derived from sugarcane, corn, or potato starch. A PET bottle that contains a mix of petroleum and plant-based feedstocks, like the Dasani and Coca-Cola PlantBottle that includes 30% bioplastic content is also just as recyclable (with cap on, please). Just like conventional plastic packaging too, bioplastic packaging can have a recyclable base material, like bio-PE, but be made unrecyclable through problematic adhesives, coatings, barrier layers, and colorants, among other factors.

Appropriately, many drop-in bioplastics that mirror conventional plastics can be recycled just like their petrochemical counterparts. A PET bottle made of petroleum is recyclable, and so is a PET bottle derived from sugarcane, corn, or potato starch. A PET bottle that contains a mix of petroleum and plant-based feedstocks, like the Dasani and Coca-Cola PlantBottle that includes 30% bioplastic content is also just as recyclable (with cap on, please). Just like conventional plastic packaging too, bioplastic packaging can have a recyclable base material, like bio-PE, but be made unrecyclable through problematic adhesives, coatings, barrier layers, and colorants, among other factors.

Some bioplastics that are biodegradable are also biobased and derived from plants. PLA, for example, is fit for composting at industrial composting facilities and is created either by fermenting sugarcane or sugar beets or through the hydrolysis of wheat, potato, corn, or other starches. Other biodegradable plastics are not bio-based, like BASF’s ecoflex®, a PBAT polymer that is industrially compostable and made from adipic acid and butanediol.

Often, choosing a plant feedstock for a bio-based plastic, whether biodegradable or not, is predicated on geography. In some regions, feedstocks like corn are abundant and cheap. In others, sugar beets are plentiful. Corn starch is the primary feedstock for PLA in North America, cassava is used most in Asia, and sugarcane throughout South and Central America. NatureWorks, for example, sources the corn used to create its Ingeo PLA polymer from the 300 miles surrounding its Blair, Nebraska facility.

Apart from availability, other considerations like water and land requirements to produce one ton of a given feedstock are important, as is the tons of feedstock required to produce one ton of bioplastic. To produce bio-PE, for instance, sugar beets require 5 times less water and a 6 times smaller land footprint than wheat per ton of feedstock. On the other hand, only 10.86 tons of wheat are needed to produce 1 ton of bio-PE while 27.25 tons of sugar beets are necessary to produce the same quantity.

Besides the feedstocks most commonly used to produce bio-based plastics today, a slew of lignocellulosics like bagasse, wood chips, straw, and switch grass are undergoing more research and development and are starting to penetrate the market. Futamura’s NatureFlex™, for one, is a bio-based compostable film made from wood pulp at managed plantations, including FSC-certified forests. Nevertheless, Erin Simon of the Bioplastic Feedstock Alliance explains that as the new economy bioplastics industry continues to grow, “All feedstocks will have advantages and disadvantages, so the focus should be on committing to the continuous improvement of the best available feedstock option for that technology and sourcing region.”

Today, the portion of new economy biobased production currently exceeds that of biodegradable plastics. The ratio has magnified in recent years, and projections strongly suggest that this chasm will increase considerably towards 2020 and beyond. The Institute for Bioplastics and Biocomposites’ 2016 report quantifies that in 2015, 37% of new economy bioplastics were biodegradable and 63% were biobased, but non-biodegradable. By 2020, however, biodegradable plastics will represent 18% of bioplastics production and bio-based, non-biodegradable plastics will rise to 82%.

This is not to say that because biodegradable plastics will make up a decreasing percent of all new economy plastics production that the production itself is decreasing. From 2015 to 2020, biodegradable plastics will see an estimated annual growth rate of 25%. Over these 5 years, biodegradable plastics use in non-packaging applications are expected to increase in textiles, agriculture and horticulture, as well as the automotive and transport sectors.

In a few categories, the dominance of biodegradable plastics and non-biodegradable, bio-based plastics will flip. Consumer goods, for one, is majority sourcing from bio-PET and other bio-based plastics, but by 2020 is expected to invert and be very heavily oriented towards PLA and starch blends. In contrast, the majority of bioplastics used in the automotive and transport sectors in 2015 are a cocktail of PLA, starch blends, and various other biodegradable plastics. Within 5 years, bio-PET and bio-PE will be used almost exclusively within bioplastic applications to this sector.

In a few categories, the dominance of biodegradable plastics and non-biodegradable, bio-based plastics will flip. Consumer goods, for one, is majority sourcing from bio-PET and other bio-based plastics, but by 2020 is expected to invert and be very heavily oriented towards PLA and starch blends. In contrast, the majority of bioplastics used in the automotive and transport sectors in 2015 are a cocktail of PLA, starch blends, and various other biodegradable plastics. Within 5 years, bio-PET and bio-PE will be used almost exclusively within bioplastic applications to this sector.

Overall, however, the majority of bioplastics production capacity will be in packaging. Flexible packaging and films in particular will experience a two-fold increase from 400,000 tons in 2015 to 814,000 tons in 2020. Yet, the majority of development will take place in the rigid packaging space where the 1 million ton production in 2015 will increase nearly 7 times to a whopping 6,897,000 tons by 2020. This non-biodegradable, but bio-based plastic will be mostly bio-PET 30, or PET rigid plastic with 30% bio-based content. Within the rigid packaging bioplastic growth, biodegradable plastics will increase from less than 200,000 tons of production capacity in 2015 to more than 1 million in 2020.

The industry production expansion makes sense when examining the corporate goals of large multinational companies and new government policies. France became the first country to ban single-use food serviceware made of conventional plastics in 2016. Starting in 2020, all single-use food serviceware will not only be required to be compostable, but home compostable, spurring new research and development for compostable plastics capable of biodegrading at lower temperatures typical to smaller residential-scale piles. This alone will drive many billions more units of compostable bioplastic items to the market and will be significantly augmented by new Italian legislation that mandates a similar home compostable serviceware requirement.

Large multinationals in the consumer-packaged goods space and elsewhere have also made progress or declared intentions to dramatically scale bioplastic use. Coca-Cola, already one of the biggest purchasers of bioplastics, has scaled bio-PET content to 30% in their PlantBottle. The company aims to continue increasing bio-PET content across more than 30 of their global brands.

PepsiCo has also made commitments to using biobased plastics in packaging. Vice President Roberta Barbieri strikes a similar note, explaining that because of the “tremendous greenhouse gas reduction benefit from bio-resins… A move to bio-based PET for our PET bottles would be a hugely impactful GHG reducing effort.” This strategy would roll up into PepsiCo’s Performance With Purpose goals, one of which is to “reduce greenhouse gas emissions across our entire value chain… by 20 percent in absolute terms by 2030.” Similarly, PepsiCo is doubling down on compostable films for its snack food packaging applications with many active pilots around the world and significant investment in Danimer Scientific to co-develop biodegradable PHA film, produced by microbial bacteria fermenting organically sourced oil. As a whole, PepsiCo has committed to distributing entirely recoverable or recyclable packaging by 2025.

Exploration certainly isn’t halting here, however, and investment in methods of transforming carbon dioxide into lactic acid, as well as methane into lactic acid, is underway. Producers of PLA are developing technologies to facilitate this process with the aim of turning greenhouse gases into compostable polymers, pushing New Economy bioplastics to new heights. Other research efforts are underway to convert materials like blood meal and feathers in addition to other animal waste products at the University of Waikato in New Zealand. Though plant proteins have long been converted to plastics, animal proteins have typically clogged extruders, University of Waikato chemical engineer Dr. Johan Verbeek discloses that “The process we’ve developed gets around that problem.” In the Netherlands, Wagenigen University researchers are forging bioplastic produced from seaweed, exploring ways that Europe can increase sustainable aquaculture where the region is only currently responsible for 0.5% of the 20 million tons of seaweed farmed globally each year.

Investigating other unconventional feedstocks, the Spanish company Ainia Technology has spent 4 years developing compostable PHB derived from the wastewater of fruit juice producers. Dr Ana Valera, associated with the Ainia project, shares that “The juice industry generates a lot of wastewater streams: for cleaning the fruit in different points, for cleaning the equipments used for manufacturing the juice, etc.” But, of the many options, the stream with the highest load of sugars, “was one from the cleaning process after the juice manufacturing.” While not yet tested in a pilot plant, the project represents an enticing plan to introduce food waste back into the economy as a circular material.

While mostly in beta phases, this incredible diversity of R&D in new feedstocks, particularly feedstocks like waste and emissions, reflect a strong commitment to getting materials that are currently escaping the circular economy back into a loop. The excitement that this generates is understandable. Yet, it should not eclipse parallel measures for packaging producers and brand owners to make space in their portfolios for recycled content.

Similarly, it’s critical to ensure that even when using a bioplastic that no confounding colorants, inks, labels, adhesives, fillers, barrier layers, or other amendments are made that compromises the recyclability or compostability of the package. And, as new economy bioplastic production increases year by year, the industry must make renewed efforts to communicate clearly to consumers.

The rising tide of bioplastics as a whole underscores unique ways to sequester carbon, transition from petroleum-based plastics, and create new products from waste. So, as research and production expansion occurs, the frenetic growth of bioplastics must also be tempered with reinvigorated communication to consumers about end of life, as well as renewed emphasis on sustainable sourcing as bioplastic feedstocks become more varied and logistically intensive. In all likelihood, responsible application of bioplastics in packaging and elsewhere will continue to lower cost and increase efficiency of production, catalyzing the transition to fossil-free packaging.

California Safe Soil graciously hosted attendees of the 2017 Green Sports Alliance Summit for a tour at their processing facility located outside of Sacramento. Founder of California Safe Soil Dan Morash walked us through the operational and logistics considerations for their food waste recycling solution, which produces an organic liquid fertilizer. Currently, most of California Safe Soil’s feedstock is commercial food waste procured from grocery stores, which on average produce 600 lbs. of fruit and vegetable waste every day.

Incoming loads of food waste from local grocery stores are delivered in blue plastic totes each containing 850-900 lbs. Incoming material can include meat and seafood, but is largely comprised of damaged or overripe fruit and vegetables, or produce trimmings from food preparation. Since totes are transported from the grocery stores to California Safe Soil’s facility every other day, food does not begin to decompose, eliminating many operator and owner concerns about smell or vermin.

Incoming loads of food waste from local grocery stores are delivered in blue plastic totes each containing 850-900 lbs. Incoming material can include meat and seafood, but is largely comprised of damaged or overripe fruit and vegetables, or produce trimmings from food preparation. Since totes are transported from the grocery stores to California Safe Soil’s facility every other day, food does not begin to decompose, eliminating many operator and owner concerns about smell or vermin.

Dan Morash, Founder of California Safe Soil explains that incoming food waste will go through three major phases of processing before sale as liquid fertilizer: digestion, pasteurization, and stabilization. Each batch can accommodate 24,000 lbs of food waste and California Safe Soil can produce up to three batches a day if operating at full capacity. The final fertilizer product is transported in a liquid tank truck to a distributor and then brought to farms throughout coastal California and California’s Central Valley.

Dan Morash, Founder of California Safe Soil explains that incoming food waste will go through three major phases of processing before sale as liquid fertilizer: digestion, pasteurization, and stabilization. Each batch can accommodate 24,000 lbs of food waste and California Safe Soil can produce up to three batches a day if operating at full capacity. The final fertilizer product is transported in a liquid tank truck to a distributor and then brought to farms throughout coastal California and California’s Central Valley.

Incoming food waste is deposited in the hopper, where material is distributed evenly onto a sorting line.

Incoming food waste is deposited in the hopper, where material is distributed evenly onto a sorting line.

Rigid and flexible plastics that are mixed in with the food are removed by hand as they are loaded into the hopper and funneled into the sorting line.

Rigid and flexible plastics that are mixed in with the food are removed by hand as they are loaded into the hopper and funneled into the sorting line.

Grinders prepare incoming fruit, vegetables, and other food to be digested. Crushing food into smaller pieces, the grinders ensure streams are as consistent as possible by grinding to half an inch.

Grinders prepare incoming fruit, vegetables, and other food to be digested. Crushing food into smaller pieces, the grinders ensure streams are as consistent as possible by grinding to half an inch.

The digester receives a uniform slurry of food waste, which is heated to 130 degrees to process pectin. The biochemical reaction uses enzymes and heat to break down fibers and composition of the material. After processing, about 80% of the material is fructose or glucose.

Once digested, material is passed through a series of screens. Here, any labels or stickers that tagged along with produce through grinding and digestion will be screened out.

Once digested, material is passed through a series of screens. Here, any labels or stickers that tagged along with produce through grinding and digestion will be screened out.

Once passed through coarse and fine screens, the remaining solids are sold as pig feed. Following the waste hierarchy to feed animals before recycling food, pigs are nourished and reliance on foreign soy imports for hog feed is diminished.

Once passed through coarse and fine screens, the remaining solids are sold as pig feed. Following the waste hierarchy to feed animals before recycling food, pigs are nourished and reliance on foreign soy imports for hog feed is diminished.

Lastly, before the liquid fertilizer is ready for field-application, it goes through a period of pasteurization for 30 minutes at 160 degrees and a period of stabilization.

Lastly, before the liquid fertilizer is ready for field-application, it goes through a period of pasteurization for 30 minutes at 160 degrees and a period of stabilization.

With the facility zoned as a rendering operation and suitable for siting in a dense urban area, transportation of food waste from groceries to California Safe Soil is convenient and not burdensome. After two years in a pilot phase in a different area of Sacramento, California Safe Soil has been succeeding in providing a waste diversion service and producing an agricultural product for the wider Sacramento area in their current facility for the past year. With eyes on the East Coast, California Safe Soil will be building a facility in New Jersey, providing the Garden State with a second option to recycle food waste with only one composting facility permitted to receive food waste in the entire state. With less demand for hog feed in New Jersey, California Safe Soil will instead produce a ratio of 80% liquid fertilizer and 20% nutrient-dense material suitable for dog food.

Paris

SPC Members,

At the Sustainable Packaging Coalition, we often find ourselves acting as a voice for our industry. It’s a role we take on seriously and with humility. And now, perhaps more than ever, we find it critical to publicly underscore our enduring commitment to the Paris Climate Agreement.

It’s clear to us that the SPC is uniquely poised to drive momentum towards the greenhouse gas reduction goals set out in the Paris Agreement. As a gathering place for the sustainable packaging community, our members not only have lofty ambitions, but they also have a means and the will to provoke change.

Acknowledging the pivotal role that American retailers, brands, packaging manufacturers and raw material suppliers have in reshaping our carbon landscape, the SPC will continue acting as a nucleus for innovation in sustainable packaging with a renewed intensity.

After more than a decade of success proving the impact of private sector action in sustainability, we have no doubt that our collective capabilities and focus will kindle the change that’s needed.

Resolutely,

Nina Goodrich

SPC Director

Food waste has catapulted from a niche concern to a topic of widespread public interest over the past couple of years. These 6 companies have found creative solutions to this pressing issue.

Patagonia’s Clean Color Collection

The latest manifestation of Patagonia’s promise to “build the best product” and “cause no unnecessary harm” has emerged as an experimental line of clothing using plant-based dyes. Patagonia’s Senior Material Research & Innovation Manager Sarah Hayes explains that “Using eco-friendly dyes is a key area of focus right now as, traditionally, dyeing is a water-intensive process can involve chemicals we want to avoid.”

Hayes’ team spent three years testing and developing the dyes before introducing the Clean Color Collection to market. Sourced from 96% renewable materials, the dyes showcase the natural pigments of food waste like pomegranate rinds that produce a rich yellow brown and the peels of bitter oranges that produce a rich brown color, as well as other materials like mulberry leaves, palmetto green, and carmine.

While the collection is still in its early days, Patagonia’s Clean Color Collection has the potential to expand consumer awareness about the limitless applications for food waste.

Condiments at Rubies in the Rubble

Started in 2011 by Jenny Dawson Costa, Rubies in the Rubble provides creative chutneys, relish, ketchups, and condiments to a growing customer base they describe as “the chutney champions, the leftover lovers, and the food-waste fighters.”

Started in 2011 by Jenny Dawson Costa, Rubies in the Rubble provides creative chutneys, relish, ketchups, and condiments to a growing customer base they describe as “the chutney champions, the leftover lovers, and the food-waste fighters.”

Offering quirky flavor combinations like Top Banana, as well as Fiery Tomato, the UK-based outfit sells condiments squarely in the $4-6 range and uses perfectly edible, but aesthetically imperfect fruits and vegetables.

Rubies in the Rubble also actively seeks out partners to collaborate on site-specific solutions and flavors. One recent partnership between Rubies in the Rubble and Virgin Trains, a UK-based train company, transformed surplus fruit from trains to apple chutney now served on Virgin Train’s first-class menu. A holiday collaboration with Fortnum & Mason, a 300-year-old foodstuff and home goods store, salvaged wonky pears from local Tendring Fruit Farm to produce a limited edition Pear, Fig & Port spread.

Across their varied product lines, Rubies in the Rubble connects consumers’ purchases to on-the-ground environmental benefits every month. In March, for instance, their website broadcasts that the equivalent of 6,708kg of CO2 has been diverted by repurposing 1,020 curly cucumbers, 5,100 over-ripe tomatoes, and 1,900 pink onions.

Toast Ale: Beer Made With Surplus Bread

Founded by Tristram Stuart, mastermind behind renowned British food waste organization FeedBack, Toast Ale capitalizes on the 44% of bread produced in the UK that goes to waste. Bread is combined with malted barley, replacing approximately ⅓ of the grain typically used in a given recipe.

Founded by Tristram Stuart, mastermind behind renowned British food waste organization FeedBack, Toast Ale capitalizes on the 44% of bread produced in the UK that goes to waste. Bread is combined with malted barley, replacing approximately ⅓ of the grain typically used in a given recipe.

While Toast Ale began by sourcing day-old bread from bakeries across London, they currently partner with Adelie Foods, which produces 3 million sandwiches a week that generate tens of thousands of crust-covered “heels” of leftover sandwich bread. More recent collaborations stay true to their locally-sourced beginnings with operations in Bristol, Devon, Sussex, and London that help local breweries partner with local bakeries to develop interesting beers.

Though the first to bring the concept of bread-based brews to scale, Toast Ale acts far from territorial. In fact, they are intent on provoking a “rev-ale-ution” and have encouraged newcomers to the space including UK-based “Wasted,” a pear farmhouse ale, a US-based brew dubbed “Loaf,” and “Bammetjes Bier” from the Netherlands.

Regrained: Eat Beer.

Regrained: Eat Beer.

ReGrained founders Daniel Kurzrock and Jordan Schwartz admit that their first foray into home brewing may have had something to do with the fact that they were underage, yet thirsty, students at UCLA. And, while they couldn’t purchase beer, they could purchase the ingredients.

Amazed at the quantity of grain leftover after their first brewing endeavors, Kurzrock and Schwartz decided to bake bread with the byproduct, which has evolved into a full-time business serving as “a go-between the brewing industry and local food systems” and specializing in Supergrain Bars.

Today, their product includes flavors like Honey Cinnamon IPA, Coffee Chocolate Stout, and Honey Almond IPA Bars. Not only is “spent grain” far from spent, the ReGrained team advocates, but “spent grain” is healthier than the original grain since almost all of the grain’s sugar is extracted in brewing, leaving a great source of dietary fiber and plant protein left.

Misfit Juicery

Misfit Juicery

Another brain-child of college students, Misfit Juicery came into being when Ann Yang and Philip Wong borrowed a blender and purchased four crates of surplus peaches from a Washington, D.C. farmers market. Yang and Wong discovered that retooling “ugly fruit and vegetables” into cold-pressed juices was an effective way of camouflaging their imperfections while highlighting their greatest attribute: taste.

Permeating the DC market before expanding to New York City and throughout the tri-state area, Misfit Juicery now distributes at more than 50 locations, including the cafe at Dan Barber’s Michelin-starred Blue Hill at Stone Barns in Tarrytown, NY.

Currently, Yang and Wong are fine tuning projections for the discounted rate they can expect from purchasing unaesthetic produce, generally ranging from 25-60% of top-shelf alternatives. Similarly, the duo is experimenting with ways to provide consistent classics like their cold-pressed juice hits Pear to the People, Offbeat, and 24 Carrot Gold, as well as providing seasonal variety.

CommonWealth Kitchen’s Mighty Muffin

CommonWealth Kitchen’s Mighty Muffin

The Mighty Muffin evolved from a request by Boston Public Schools (BPS) to the local food business incubator for a new breakfast item for students, CommonWealth Kitchen. While participating in the incubator, Meg Crowley developed a recipe that fit the bill of a muffin that was delicious, but also low in sugar, high in fiber, and nutritious. Crowley accomplished this tall order by creating a new use for the by-product from the carrot peels, tomato ends, and celery tops that a Baldor Specialty Food location in Boston generated.

Once dehydrated, these scraps once destined for a landfill could serve as a 25% substitute of the whole wheat flour Crowley used to make the muffins. In further efforts to build nutrition and rescue food, surplus produce like zucchini, apples, squash, and carrots are also incorporated.

With 78% of BPS students qualifying for free or reduced lunch, BPS has participated in a federal program to offer breakfast, lunch, and an after-school meal to every student free of charge. Since this transition in 2013, BPS has searched for more local and regional partners to work with and has inadvertently acted as a catalyst for scalable and replicable food waste solutions.

This summer, Jessica Edington joins the GreenBlue team as a project associate focused on the How2Recycle label program. Jessica comes to GreenBlue with a background in sustainability consulting in the Washington, D.C. area.

This summer, Jessica Edington joins the GreenBlue team as a project associate focused on the How2Recycle label program. Jessica comes to GreenBlue with a background in sustainability consulting in the Washington, D.C. area.

What inspired you to work in the sustainability field?

I grew up on the Chesapeake Bay, and as a child I would participate in the Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s Clean the Bay Day, where we would row out in canoes and collect litter from the creeks and marshes. I was blown away by the sheer quantity of garbage we collected from such a small area. The experience left a big impact on me, and I knew from a young age that the way Americans deal with waste was a problem and that recycling was one way to fix it, but beyond that I was admittedly pretty ignorant. Years later, while studying English at the College of William & Mary, I decided I wanted to know more about how to “save the environment” and so I spent a semester living in an eco-village in Iceland, studying sustainability. It was here that I really learned about the vast complexity of the underlying systems and challenges we face trying to affect sustainable change in our communities and our planet. My time in Iceland launched my exploration into the many different areas of sustainability, from agriculture to energy to education, and my continued passion for working in the field.

What do you find most challenging?

For me, and I think probably for many people, the most challenging aspect of working in sustainability is not getting overwhelmed and giving into despair when constantly confronted with the scale of issues such as climate change. You have to constantly remind yourself that even the small efforts and small changes, in aggregate, do add up to make a difference.

What do you hope to achieve at GreenBlue?

When I walk into a grocery store, I want to see the How2Recycle label on everything! And not just the national brands with wide reach, but the smaller and “generic” brands as well, because I think that consumers who might have to choose a more economical option should have access to accurate, clear recycling information as well. I would also like to see the How2Recycle label grow an even greater presence in products like toys, electronics, home goods, and e-commerce.

What is the one thing you would like people to know that you do in your personal life to further sustainability?

I tried my hand at a backyard garden once, but my lack of a green thumb meant that failed miserably, so now I opt to get my produce from the farmer’s market while it’s in season, and support local and small-scale agriculture whenever possible.

Favorite outdoor activity

I love anything involving trees — climbing trees, planting trees, walking among trees, setting up a hammock and napping beneath trees…

Happiness is….

Found most often in the simple moments: a cup of tea with honey on a chilly morning; belly-laughing with my husband at our dog’s silly antics; the shade of light filtered through leaves on an afternoon stroll; knitting a cozy wool hat for a loved one.

The circular economy has undeniably become the trendiest business buzzword in the conversation on packaging sustainability. Building on established themes like zero waste, cradle-to-cradle design, and closed loop systems, the philosophical framework is simple: in a circular economy, we don’t extract virgin non-renewable resources and we don’t generate waste. Instead, industrial outputs become new inputs, and thus some of the environmental burdens of resource extraction and solid waste disposal are averted.

In the world of packaging, circular economy thinking owes much of its popularity to the visual and visceral presence of packaging waste. Companies are doubling down on innovations to alter or improve the recyclability of their packaging. Consumers want to able to recycle, reuse, or compost packaging, and the circular economy model fits with consumer expectations of corporate responsibility.

Circular economy thinking focuses most heavily on material sourcing at the beginning of the life cycle and recovery at the end of life, and although this focus is proving to be an effective catalyst for industry action, it’s important not to lose sight of the overarching considerations for the whole life cycle – including the middle. Circular economy thinking should be paired with life cycle thinking and the “sister” philosophical framework of sustainable materials management. Doing so gives more context to the net environmental impacts resulting from the life cycle of a package, placing emphasis on the outcome of the life cycle in addition to its shape. Together, these approaches promote pragmatic, meaningful gains in impact reduction along with the long-term vision of a materials economy devoid of packaging waste.

At SustPack 2017, our panel discussion on Demystifying Packaging Metrics and KPIs explored ways of benchmarking and measuring progress toward both circular economy and sustainable materials management ideals at the beginning and middle of the life cycle. A key takeaway from the session is the necessity of a suite of key performance indicators (KPIs) working in concert to help guide progress.

Jason Pelz, vice president of environment at Tetra Pak, a food processing and packaging solutions company, shared the set of indicators being used by the aseptic and gable top carton producer. To address circular economy thinking on the feedstock side, Tetra Pak tracks the percentage of renewable feedstock materials used to make a package and the level of assurance that those materials were responsibly grown and harvested. On the recovery side, Tetra Pak measures the percentage of consumers that could recycle their product, i.e., those with a municipal program that can process their cartons, as well as the percentage of cartons that are recycled. On the sustainable materials management side, Tetra Pak places emphasis on greenhouse gas emissions incurred by both their operations, toward the beginning of the packaging life cycle, and greenhouse gas emissions incurred across the value chain, appropriately addressing the full packaging life cycle and the carbon footprint of the holistic system of using Tetra Pak’s cartons.

When companies are advised to craft and use a set of KPIs to measure sustainability, a common refrain is “Why so many? Isn’t there such a thing as a single unified metric?” The answer is always no.

We’re all tempted to pursue a mythical singular metric that distills all the numerous sustainability considerations and gives one bottom line measure of success, but a suite of KPIs such as those used by Tetra Pak gives a robust view of progress in the multiple dimensions of sustainability. Furthermore, attention will continue to shift across impact areas, and using a suite of KPIs grants flexibility that can keep industry nimble as the understanding of sustainable packaging evolves. Today, resource management and greenhouse gas emissions are the foremost life cycle indicators. In a few years, it may be water consumption, aquatic toxicity, particulate emissions, solid waste to landfill, or something not at all on our radar today. That shouldn’t be intimidating or prohibitive of establishing metrics. The most important action a company can take to improve packaging sustainability is to create KPIs and use them, like Tetra Pak is doing, to ingrain a system of measurement and management around their processes. Change will come and go, but the idea of a systemic approach to gauge success and progress is here to stay.

Don’t let it go to waste

Americans generate 65 million tons of food waste annually. Could compostable packaging aid in recovering significant amounts of food scraps for composting?

Composting may seem like a new phenomenon, but commercial composting operations have been in business in the United States since the late 1980s. While many people are familiar with backyard composting — collecting kitchen food scraps to be composted in one’s backyard or setting yard trimmings curbside to be composted by municipalities; modern composting operations are more complex. There are nearly 140 active commercial composting facilities in the United States producing rich soil amendments (the end product from the composting process). These facilities process a variety of compostable items, such as yard trimmings, food scraps, and packaging.

Still in its infancy, commercial composting is growing rapidly, due to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) goal to reduce food waste nationally by 50% by 2030 from a 2010 baseline. A study commissioned by ReFed, a non–profit organization, analyzed the best opportunities to reduce food waste in the U.S. Their groundbreaking report determined that centralized composting was the best option, surpassing 26 other solutions to food waste management when comparing waste diversion and emissions reduced.

Still in its infancy, commercial composting is growing rapidly, due to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) goal to reduce food waste nationally by 50% by 2030 from a 2010 baseline. A study commissioned by ReFed, a non–profit organization, analyzed the best opportunities to reduce food waste in the U.S. Their groundbreaking report determined that centralized composting was the best option, surpassing 26 other solutions to food waste management when comparing waste diversion and emissions reduced.

In areas with centralized composting facilities, challenges still exist. Many composters do not accept compostable packaging, claiming to only want the “good stuff,” also referred to as pre-consumer food scraps (pictured right). Composting facilities will often refrain from collecting post-consumer food scraps and compostable packaging because they believe it will lead to greater levels of contamination. Such contamination can complicate the composting process as non-compostable items will not adequately break down within the commonly used covered aerated static pile system. But refusing to collect compostable packaging might be costing composters a sizable source of food scraps.

There is some anecdotal evidence to support the hypothesis that compostable foodservice packaging significantly increases food scrap diversion. However, few controlled studies have been conducted to specifically measure a relationship between compostable foodservice packaging and food scraps diversion.

The Sustainable Packaging Coalition conducted a study in 2016 to explore how and if compostable packaging can increase food waste diversion rates; bringing more food waste to composters. The study determined the proportion of food to packaging in front-of house areas, as well as how much food was captured in both back-of-house and front-of house areas.

The SPC conducted waste characterizations at five venues, and the results were striking. It was found that compostable packaging could achieve a food scrap capture rate of 35-86% in front-of house areas. Oftentimes, composters do not collect food scraps from front-of house areas due to the possibility of contamination by the public. But at the largest music venue in the study, FarmAid at Jiffy Lube Live Pavilion, all the packaging was compostable, but less than half of the total amount of food scraps were generated in back-of-house areas. Therefore it was determined that packaging served as a vehicle to bring front-of house food to the compostables bin. The study did not account for contamination, the data captured the max capacity for food scrap capture in an ideal environment, in which all waste materials were sorted properly.

The SPC conducted waste characterizations at five venues, and the results were striking. It was found that compostable packaging could achieve a food scrap capture rate of 35-86% in front-of house areas. Oftentimes, composters do not collect food scraps from front-of house areas due to the possibility of contamination by the public. But at the largest music venue in the study, FarmAid at Jiffy Lube Live Pavilion, all the packaging was compostable, but less than half of the total amount of food scraps were generated in back-of-house areas. Therefore it was determined that packaging served as a vehicle to bring front-of house food to the compostables bin. The study did not account for contamination, the data captured the max capacity for food scrap capture in an ideal environment, in which all waste materials were sorted properly.

Composters are reasonable to fear that collection of front-of-house food scraps can lead to small amounts of contamination, and ultimately lead to costly decontamination processes. Many composters are unwilling to jeopardize the quality of their soil amendment, which often represents the bulk of their revenue. The SPC hopes this study will show composters the potential gains from allowing more packaging into their collection streams. The significant increases in food capture will help offset the cost of decontamination, and ultimately help consumers become more aware and engaged in composting efforts. This is only the start of the conversations with composters, and serves as the beginning for re-evaluating compostable packaging as an asset, not a determent to the compost industry.

Compostable packaging will play a significant role in achieving the EPA’s food waste reduction goal. While 7% of composters already accept compostable packaging, wider adoption is needed to divert additional material. With proper labeling on packaging through the new How2Compost label, contamination can be reduced.

Stay tuned for the release of the SPC’s full Value of Compostable Packaging report later this month.

It’s promising for our future if a sustainability philosophy (circular economy) gets significant attention at a televised global meeting such as the glossy World Economic Forum in Davos. If the “jet-setting C-suite” is now privy to the fact that sustainability could potentially be the best way to mitigate risk in an increasingly complex world (such as partially outlined in Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s The New Plastics Economy: Catalyzing Action report), it means that we can at least have hope that business leaders will rise to fill the void created by the world’s governments facing identity crises and/or those unable or unwilling to make systemic change.

So the fact that over 40 global corporations and organizations have signed on the New Plastics Economy (as well as the similar-in-spirit but different Business Backs Low Carbon) means there is reason for tempered, if not earnest optimism. It is in many ways a relief that a single report is able to capture and explain the momentum around reconceptualizing plastics that has been crystallizing within many organizations and companies for several years now, and point to specifically what that might look like. These important considerations haven’t had quite as broad and deep an audience until the formation of the New Plastics Economy.

On the other hand, it’s no true surprise that an initiative as forward thinking and smart as circular economy, designed and talked about in such a charismatic and compelling way (with pretty PDFs and dynamic web experiences via Ellen MacArthur Foundation and IDEO) would capture the hearts of many.

The flipside to this sense of promise and ambition is the sobering realization that despite dazzling visualizations that demystify potential reuse cycles for plastics or show how to drastically reduce leakage of them into the ocean—the professionals “in the trenches” of packaging sustainability still have to find an actual means to make these enormously large and complicated challenges fathomable, surmountable. In other words, we have to find a literal real life way to make it all work.

Sustainable Packaging Coalition (SPC) is the organization best poised to make many of the New Plastics Economy’s most recent recommendations a reality.

For 13 years, the Sustainable Packaging Coalition (SPC) has empowered industry to blaze its own path towards well-designed solutions that reflect on-the-ground sustainable packaging realities. Over 175 companies are members of SPC because they know that building resilient, circular packaging requires knowing the context of one’s work, specifically how to use sustainability to create value, and what parts of the future you can not only forecast and prepare for, but proactively design. We do that by facilitating conversation, encouraging harmonization, and analyzing and sharing information. Coincidentally, these are the ‘building blocks’ that the Catalyzing Action report precisely calls as necessary.

This means that SPC is an information broker (such as EPAT, SPC’s Centralized Availability of Recycling study), a tool builder (such as Landscape Assurance Model, How2Compost), and a innovation facilitator (for example, evolving the notion of ‘bioplastics’, taking a position against biodegradability additives).

There are a few SPC projects that are particularly well suited to make the New Plastics Economy a reality—especially where the report talks about the need for feedback loops. Specifically, it recommends, “To successfully implement the [packaging] design changes [required for recyclability], communication between packaging designers at the front end and the after use processors at the back end is an important enabler. Such feedback loops would also help to understand further design-improvement potential.”

One of SPC’s projects that exactly meets this description is the on-package recycling label system that is changing consumer behavior and being leveraged to inspire design change: How2Recycle.

How2Recycle is a feedback mechanism that is changing packaging design and consumer behavior in several ways. First, the How2Recycle label equips its members with accurate and credible information about the recyclability of their packaging. The Catalyzing Action report says industry should “implement design changes in plastic packaging to improve recycling quality and economics (eg choices of materials, additives, and formats).” The How2Recycle decisionmaking process already takes this spectrum of issues into consideration when it issues each How2Recycle label, so that each package reflects a custom recyclability assessment.

As long as the penetration of the How2Recycle label continues to proliferate in the marketplace, which is informed by the expertise of the APR Design® Guide for Plastics Recyclability and other industry experts, How2Recycle will continue to drive incentives for specific packaging design improvements. Our members tell us that the How2Recycle label triggers internal conversation about recyclability, gives brands an easy way to talk about recyclability with suppliers, and broadens perspective on material and format choices.

Second, How2Recycle is building an online platform for its members that will enable brands to track the recyclability of their packaging portfolio, meaningfully interpret what that means, and then be provided specific, dynamic feedback for them to improve. This could become a critical tool if companies embrace it in order to measure progress towards and eventually hit their emerging corporate recyclability goals.

Third, How2Recycle is a critical feedback loop because it facilitates peer-to-peer competition. With over 60 companies that represent over 500 brands in the marketplace, How2Recycle members are able to see how the recyclability of their packaging stacks up against others’. In some cases, these comparisons create easy opportunities to make design tweaks to get a “better” How2Recycle label. Voluntary programs like How2Recycle that are based on transparency push the entire industry forward.

Fourth, How2Recycle’s influence doesn’t only flow towards brands, but also in the other direction—towards the general public. If 67% of consumers assume that packaging isn’t recyclable if they don’t see a recycling claim on the package (Carton Council, 2016), and if 50% of consumers tell us in our survey that they are changing their behavior as a result of How2Recycle, this means How2Recycle’s actual and potential future impact is significant. Our data suggests that consumers are not only recycling more because of How2Recycle, but recycling more accurately. For example, How2Recycle’s “Empty & Replace Cap” message on plastic bottles adds an important level of detail so that the caps are far more likely to be recovered and don’t end up as litter—especially in the ocean. Additionally, the Not Yet recycled label helps consumers know what they should not recycle, which reduces contamination at recycling facilities.

How2Recycle is not the only SPC project that supports the idea of a new plastics economy.

Importantly, SPC events such as SustPack and SPC Advance (each fall) transcend traditional silos along the value chain; these conferences bring hundreds of companies into the same room in order to hash out the detailed opportunities and challenges in packaging sustainability. For example, Amazon’s presentation at SustPack in April explored how to design packaging for e-commerce that reduces waste and minimizes damage. In turn, SPC events allow our members to benchmark themselves against the innovation curve. This information means that the professionals within SPC companies can make the internal argument to acquire better resources to accomplish more work—once they understand what industry leadership is looking like and what they need to do in order to stay innovative.

SPC also offers The Essentials of Sustainable Packaging customized training courses that provide companies a comprehensive introduction to sustainability considerations across the packaging life cycle: sourcing, design, recovery, and beyond. By traveling to brandowners’ headquarters, SPC staff talks to design and sustainability teams about how to balance tradeoffs in packaging design considerations and analyze attributes such as forest certification or recycled content. Through this course, SPC is setting companies free with critical information to make their circular economy ambitions come to life.

ASTRX, Applying Systems Thinking to Recycling, is a joint project between SPC and The Recycling Partnership. This new initiative will build a roadmap for a stronger American recycling industry by diving deep into how materials flow through each of the five elements of recycling: end markets, reprocessing, sortation, collection, and consumer engagement. To increase recovery, ASTRX will examine each element of the recycling system, identify barriers to recovering more high quality materials, and develop solutions that support each element and thus help the recycling system as a whole.

The Catalyzing Action report also calls for “scaling up compostable plastics in order to capture nutrient-contaminated packaging.” SPC’s parent nonprofit, GreenBlue, has developed the Composting Collaborative—a group that unites composters, consumer-facing businesses, and policymakers to accelerate composting access and infrastructure in North America. Additionally, SPC will release findings this spring from the Value of Compostable Packaging measurement project, that demonstrates to what extent compostable packaging can play a role in capturing food waste that would otherwise go to landfill.

SPC has both the vision and the means to make the future of new plastic real.

But in order to truly make it all work, as a collective, we have to wade through the Everglades. We have to lay down transatlantic fiber optic cables with our bare hands. This sort of work requires self-awareness, humility, and discipline.

Kelly Cramer wrote a companion piece to this article that can be found on GreenBiz.

Building up trust in recycling

It has taken decades to build up a culture and an infrastructure to support recycling in the United States. Every Tuesday like clockwork, my neighbors line up their blue carts of recycling next to their green carts of trash. For many people, recycling is as easy as filling up your cart and wheeling it to the curb. Unfortunately this isn’t the case for everyone. Some people have community drop-off sites for recycling and some have no access to recycling at all. Even in those communities where recycling is available, we don’t all have the ability to recycle the same types of products, creating confusion. So how do we know if the work done by all of our recycling leaders to create a recycling system in the United States has been successful and if it’s sustainable?

The panel on Building Trust in Recycling at SustPack 2017, which included panelists Derric Brown of Evergreen Packaging, Keefe Harrison of The Recycling Partnership, and Susan Robinson of Waste Management, tackled this and other questions about the current status and the future of recycling. As the panelists discussed, recycling isn’t easy. While brands and retailers have well-organized distribution systems to supply consumers with products, recycling is essentially returning those materials back to the marketplace through reverse logistics using a complex chain of 20,000 different local governments, over 200 material recovery facilities, and untold numbers of reprocessors and end markets. Creating a system in which all of these different entities can work together takes a lot of effort.

So how do we know if the recycling system is working? Traditionally, local governments have measured their recycling programs using weight, specifically, the tons of material diverted from the landfill. This measurement is easy to collect and makes sense to residents. As mentioned by the panel, another option is to use life cycle assessments (LCAs) as a way to measure the success of recycling. An LCA is a model that assesses the environmental impacts of a product or package from raw material extraction through disposal or recycling.

LCAs are complicated. A number of different pieces of data go into them, and the user can set up the parameters of each LCA differently. The outcomes of an LCA, like the eutrophication potential of a product, can be esoteric to the average consumer. As one panelist said, it would be hard to explain an LCA for recycling to residents. The outcome of an LCA depends on the data and parameters used to complete the model, making the results of one LCA difficult to compare to the results of someone else’s LCA.

While LCAs may be a valuable tool to help understand the carbon impacts of products, they should not be the sole measurement tool for solid waste management. LCAs can be used in addition to the measures already available to us, such as weight-based measures of landfill diversion, as well as waste characterization studies and measures of how much of our recyclable materials make it to the recycling cart instead of the trash cart.

So while we’re not yet able to measure the success of recycling with a single metric, what the recycling system does have going for it is that consumers really want it to work – they want to recycle and they expect to be able to recycle easily, both at home and away from home. As one panelist mentioned, when a material is removed from their recycling mix, they feel a sense of betrayal. When word spread in my community that glass might be ending up at the landfill after going to the MRF, my neighbors took to our neighborhood listserv to express their frustration that they were taking the time to recycle glass but it was not actually being recycled. But others wanted to find ways to keep recycling glass, like taking it to drop-off sites. Because people know that recycling benefits the environment, and they want to contribute.

We should continue to discuss how to measure the success of recycling, including how best to use landfill diversion, capture rates, and LCAs to understand our impacts. But we should also keep in mind the less measurable impacts of recycling, such as empowering consumers to take action that benefits the environment.

Ah, spring. Time to enjoy the warm weather … and take on some of the cleaning tasks you’ve been putting off all winter. But did you know that the cleaning products you choose can affect the air quality inside your home?

Americans, on average, spend approximately 90 percent of their time indoors, where the concentration of pollutants is often several times higher than outdoor concentrations. This can be a particular concern for vulnerable populations, such as the very young, the elderly, or people with existing health conditions, who are both more vulnerable to the effects of pollution and may spend even more time indoors.

Indoor air pollution can come from a wide range of sources, including volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the products you use, as well as off-gassing from building materials (like pressed wood products that can emit formaldehyde), combustion of wood or fossil fuels in fireplaces or appliances, intrusion of radon or VOCs from subsurface contamination into the building, and even mold. The problem can be exacerbated by modern building techniques, which seal the building from air leaks to promote energy efficiency, but can reduce indoor air quality if there isn’t appropriate ventilation.

Short-term and long-term health effects associated with poor indoor air quality depend on the specific contaminants present. For example, VOCs can contribute to asthma; eye, nose, and throat irritation; headaches, loss of coordination, and nausea; damage to the liver, kidneys, and central nervous system; and even cancer. Indoor air quality can also affect your cognitive function and ability to concentrate, so maintaining high indoor air quality is critical for schools and workplaces as well as homes.

So, what can you do to improve the air quality in your home? One of the easiest steps you can take is to choose safer formulated products, such as cleaning products, thereby reducing sources of indoor air contaminants. Since many conventional cleaning products are high in VOCs and other potential air contaminants, it is important to choose safer low-VOC products to use in your home. Even cleaners made from natural materials can contribute to indoor air quality problems. For example, cleaning products that contain terpenes (e.g., pine or citrus oils) can react with ozone (either from outdoor pollution entering the building or from ozone generators sold as air cleaners) in the air within your home to produce formaldehyde, fine particulate matter, and other pollutants.

When shopping for household cleaners, look for products with the EPA Safer Choice label. These products are required to have lower levels of VOCs to reduce impacts on indoor air quality, plus all ingredients have been screened by EPA and are safer for your family’s health and the environment. The Safer Choice program follows the VOC standards for consumer products established by the California Air Resources Board (CARB) and the Ozone Transport Commission. These agencies set VOC content limits for personal care products, cleaning products, adhesives, aerosol paints, and more based on the type of product.

Other steps you can take to improve indoor air quality include using paints and other household chemicals with low VOC content, avoiding dry cleaners that use hazardous solvents such as perchloroethylene, and avoiding new building materials such as particle board, plywood, and medium-density fiberboard (often used in subflooring, cabinets, or furniture). If you must use these materials in your home, ensure that adequate ventilation is present. In addition, some studies suggest that houseplants can improve indoor air quality; however, their effectiveness in real-world situations is uncertain.

Indoor air quality is a serious concern. One of the simplest things you can do to improve indoor air quality is to choose safer products that are lower in VOCs – so when you do your spring cleaning this year, look for the Safer Choice logo and enjoy the fresh air indoors and out!