Packaging development is slow, expensive, and hard. The four panelists speaking to Alternative Tech and Packaging at SustPack 2017 underscored this reality and called on the industry to get smart and do it fast.

Frankly, there’s a lot at stake. Dr. Andrew Hurley, Assistant Professor of Packaging Science at Clemson University, set the stage by explaining that an astounding 93% of new products fail within six months of entering the market. And, while packaging is only one factor that contributes to the success or failure of products, it’s a big factor. There is an enormous amount of time, effort, and resources going into a process and product that’s never fully realized.

Today, Hurley explained, most packaging design choices are made by gut-feel. It’s amazing to think that in this day and age, with incredibly powerful tools at our disposal to track eye movement and gather biometric data, we’re still making decisions like Don Draper on Mad Men. All that’s missing are the old fashions.

After conducting more than 1,300 studies with the Sonoco Institute for Packaging Design and Graphics at Clemson, though, Hurley is a clear voice that data-driven decisions aren’t out of reach. Really, they’re quite attainable. House Autry Mills’ Vice President of Marketing, Michael Ganey, is a testament to this fact. After leading a packaging overhaul of House Autry’s milled products that was guided by data Hurley’s team generated, sales increased by 5.5%. Not only was the biometric data able to guide precision decision-making on adjusting graphics, colors, and design, but Ganey reflected that it was an invaluable tool to communicate their design choices with executives. Without irrefutable data, Ganey shared, executives may be more likely to make snap decisions based on personal preferences that may not resonate with consumers.

Coming from a tech background, it is particularly apparent to Adam Harris, Director of Business Development and Innovation at Packlane, that the packaging space as a whole has yet to embrace big data. This has real implications for packaging manufacturers or brands that use packaging to be resilient in a crowded marketplace. Harris expressed that Packlane initially anticipated being most relevant to smaller operations that don’t have the expertise, time, or capital to design and source their own packaging. But, Packlane’s optimized supply chain has proved equally coveted by household names like Ghirardelli, Red Bull, UPS, and Walmart, among others.

This epiphany illustrates Harris’ claim that there are still huge efficiency gains that haven’t been realized in packaging production and distribution by publicly traded companies and start-ups alike. Interestingly, Harris compared the state of packaging supply chains today to that of taxis before Uber and Lyft came onto the scene. Taxis would respond to calls over the radio, blind to their location relative to the rider. In contrast, Packlane outsources production to manufacturers nearest the client, much like Uber and Lyft linking riders to nearby drivers.

Similarly to how Packlane enables smaller outfits to design high-quality packaging in small quantities, Tyler Matusevich, Senior Sustainability Specialist for the Americas at UPM, shared the news of a recent partnership with Finnish craft brewery Saimaan Juomatehdas. The two companies innovated together to meet the needs of small-run packages. With direct printing on Saimaan Juomatehdas’ aluminum cans a cost and capital-prohibitive endeavor, UPM transported the equipment necessary to use UPM Raflatac’s VANISH™ label on small batch craft beer. Both UPM and Packlane’s efforts to provide high quality, cost-effective, and flexible packaging solutions, have in effect democratized packaging. Without right-sized services, smaller outfits would be put at a significant disadvantage in providing striking and affordable packaging to its customers.

Similarly to how Packlane enables smaller outfits to design high-quality packaging in small quantities, Tyler Matusevich, Senior Sustainability Specialist for the Americas at UPM, shared the news of a recent partnership with Finnish craft brewery Saimaan Juomatehdas. The two companies innovated together to meet the needs of small-run packages. With direct printing on Saimaan Juomatehdas’ aluminum cans a cost and capital-prohibitive endeavor, UPM transported the equipment necessary to use UPM Raflatac’s VANISH™ label on small batch craft beer. Both UPM and Packlane’s efforts to provide high quality, cost-effective, and flexible packaging solutions, have in effect democratized packaging. Without right-sized services, smaller outfits would be put at a significant disadvantage in providing striking and affordable packaging to its customers.

In much the same way, Hurley highlights that accessible prototyping and testing is a huge benefit to companies that’s largely unrealized by the packaging industry. Hurley quips that since “Statistically, you’re going to fail. So why not get it over with?” Working through ineffective designs before mass-production by leveraging precise data and actionable feedback from testing can save large sums compared to conventional retroactive approaches to fine tune packaging designs.

The strategies illustrated by Hurley, Ganey, Matusevich, and Harris pose big questions to much of the packaging community. Will biometric data testing become quotidien in R&D? Will right-sized approaches to production and distribution activate untapped market segments? Irrespective of a company’s size, it appears that alternative tech will only become more critical to remain competitive in a crowded marketplace and CPG landscape.

Bioplastics have gained attention in recent years due to their potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and, for certain types of bioplastics, the ability to create compostable products, but functionality and cost effectiveness are critical to ensuring they can be used more widely to create sustainable solutions. At SustPack, Marc Verbruggen, president and CEO of NatureWorks, gave a fascinating update on some of the latest developments in the PLA industry.

Bioplastics such as PLA can be made from a wide variety of feedstocks, ranging from crops such as corn and sugarcane, to cellulosic materials such as wood chips or bagasse. Sustainability of a bioplastic — as well as the cost —depends both on the feedstock used and the efficiency of the conversion of the sugar in the feedstock to the polymer. PLA performs well relative to other bioplastics in conversion efficiency, but there is a great deal of regional variability. While use of cellulosic feedstocks to create second-generation bioplastics represents a newer technology, the sustainability of each feedstock must be evaluated on its own merit. For example, in Nebraska, where NatureWorks has a PLA factory, corn is readily available and may be a more sustainable feedstock, whereas in Finland, a locally-sourced cellulosic material such as woodchips may be a better choice – at least given current commercially viable technology.

While plants such as corn, sugarcane, or trees are effective at converting carbon dioxide to carbohydrates, Verbruggen suggested that they may not actually be the most efficient option. The newest technology under development involves the use of methanotropic bacteria and cyanobacteria to create lactic acid directly from methane or carbon dioxide. The resulting lactic acid can then be used to produce PLA. Although this technology is still a few years from commercialization, the prospect of a more efficient third-generation bioplastic feedstock with the potential for lower environmental impact is exciting news.

Innovative feedstocks are great, but ultimately, to gain market share the resulting plastic will need to provide functionality in creative new applications. During his session, Verbruggen shared some new potential applications for PLA. PLA can be used in a sealant web to create a product that is bio-based and compostable, and can also be lighter than a comparable polyethylene product, making it more cost competitive. In addition, PLA-based cups for dairy products such as yogurt can perform better than high impact polystyrene: they can be less hazy and have lower oxygen permeability, in addition to being compostable. Coffee pods are a third potential use for PLA. While standard PLA has not had the necessary heat resistance for this application, Verbruggen argued that crystalline PLA can stand up to the high temperatures of coffee brewing and can also provide good barrier qualities. If PLA can be used to create compostable coffee pods, it could be a great opportunity to help get coffee grounds to the composters who find them valuable in compost piles.

It is exciting to hear about the potential for new innovations in this space, ranging from the ability to create feedstocks directly from carbon dioxide and methane using bacteria to new applications where PLA has the potential to provide improved functionality during the use phase relative to traditional plastics, in addition to being sustainably sourced and compostable.

For more insight into the bioplastics industry, join us at SPC Bioplastics Converge on May 31-June 1, 2017 in Washington, D.C.

SustPack attendees toured Arizona State University’s downtown campus, led by University Sustainability Practices Program Coordinator Lesley Forst, to learn about the how the university’s waste, energy, water, and green building program initiatives contribute to cutting-edge sustainable design. Diverse sustainability efforts were illustrated by Forst and several student employees at ASU’s Office of Sustainability who expertly answered attendee questions and provided a peek at the inner workings of sustainability decision making and implementation.

As more cities begin to leverage circular economy principles to reach ambitious zero waste goals, ensuring that packaging is both recoverable and recovered will be hallmarks of any successful plan. In recent years, cities have become bolder in categorically banning or mandating certain packaging types in attempts to match what packaging is being sold or distributed and what a given city’s recycling and composting systems can currently process.

The first wave of city-led packaging bans largely honed in on foam polystyrene (PS), perceived by many cities as a problematic packaging substrate due to the confluence of several factors. Namely, the reality that less than 20% of Americans have access to recycling infrastructure for foam PS and the high incidence of PS packages and PS microplastics in marine environments. After a few of early outliers, more than 96 distinct city ordinances have banned PS since 2008.

However, in the last few years, several cities have changed tack in approaching packaging requirements. Though straight-forward bans are still being implemented in many areas, cities like Washington, D.C., Seattle, and Minneapolis have gone a step further and passed ordinances that deem recyclable and compostable packaging compliant and non-recyclable or compostable packaging non-compliant. While common in Europe, this tactic is certainly more progressive for American cities. The practice of more hands-on specifications for packaging has even permeated national governments in Europe, led by France mandating that all single-use food serviceware be home compostable by 2020.

Yet, the compliant and non-compliant packaging established by Seattle, D.C., and Minneapolis paint packages with very broad strokes. In terms of compliant packages that are recyclable, Minneapolis categorizes “glass bottles, aluminum cans and some plastic food and beverage packaging” as recyclable and names PET, HDPE, and PP as preferred plastics since robust markets exist. In a similar, but slightly more specific way, the Mayor’s List of Recyclables and Compostables for D.C. considers packaging to be recyclable if “made solely out of one of the following resin types”: PET, HDPE, LDPE, PP, and PS.

Overall, it’s exciting to see cities start to curate packaging that’s sold or distributed to match the local recycling infrastructure and note the importance of strong end markets. But, needless to say, just because a package is made of a recyclable resin, does not mean that problematic colorants, inks, fillers, labels, adhesives, additives, barrier layers, or closures render a given package unrecyclable according to the Association of Plastics Recyclers’ Design Guide. Even though PET has a strong end market, for instance, if a PET package is opaque, it dramatically reduces the resale value and is considered detrimental to recycling by APR.

Among the compostable packaging sections of these packaging ordinances, there are big differences in how comprehensively each addresses compostability. For instance, some city packaging ordinances strictly govern packages and consider the many incidental items that are associated with food serviceware to be out of scope. Minneapolis, for one, exempts utensils and straws from their Environmentally Acceptable Packaging Ordinance as “they are not packaging items”. The California county of Santa Cruz, on the other hand, is much more comprehensive in their Environmentally Acceptable Packaging Materials Ordinance, which went into effect on January 1, 2017. Santa Cruz illustrates in their guideline for restaurants that plastic straws and plastic stir sticks are unacceptable and that “all to-go cutlery must be certified compostable.”

For composters, a more holistic view is critical in mitigating contamination of post-consumer pick-ups. Principal and Managing Director of the Compost Manufacturing Alliance, Susan Thoman, elucidates that “With all the best intentions, food service operators often spend time and effort procuring compostable service ware, only to substitute what they may believe to be incidental non-compostable components to go with them.” Thoman explains that, “For instance, when appropriate compostable hot or cold cups are sourced, yet the straws and lids used with them are not compostable, the entire set is tossed into the compost collection bin, creating a significant source of contamination for the compost facility.” Justen Garrity, Founder and President of Baltimore-based Veteran Compost echoes Thoman’s thoughts, lamenting that plastic straws and stirrers are Veteran Compost’s most challenging contaminants. While Veteran Compost regularly work with clients to use compostable serviceware, they have had to force the issue when plastic straws have persisted in the organics stream.

Municipality packaging ordinances are generally thorough in detailing compostable items that are within scope, however. St. Louis Park, Minnesota, for example, communicates on their Public Works website that “Unfortunately many paper food service items are lined with plastic, so without a marking that it is compostable or other indication it is not lined, these items should go in the trash.” Moreover, the Minnesota city provides a phone number for residents to ask specific questions and encourages residents to look for signage or to ask restaurant staff. All of these strategies help prevent contamination and stimulate opportunities for further education.

Minneapolis and D.C. also demonstrate important attention to consumer education. Minneapolis’ online program materials explain why terms like degradable, biodegradable, oxo-degradable, and earth friendly are unreliable and don’t mean the same thing as compostable. D.C., on the other hand, draws attention to the fact that while foodservice operators will have to comply with their ordinance and use BPI Certified packaging starting January 1, 2018, there will be a separate acceptance list for compostable materials for all other entities and people once collection services are established in the District. This works to preempt confusion for residents that could mistakenly assume their requirements would match that of commercial foodservice operators in the near term.

D.C. also qualifies their Mayor’s List of Recyclables and Compostables by noting that “In the future, additional product and material types and processing types may be added to the list of what is required to be recycled.” In lieu of the outright ban of yesteryear, these packaging ordinances allow cities to have more flexibility and adapt to changing technologies and innovations that increase recyclability of certain packaging types in the future. St. Louis Park’s ordinance even calls out a mandate to review what packages are acceptable annually. The St. Louis Park ordinance, which was passed unanimously by City Council, is supported by one resident who clarifies that “If we just pick on polystyrene, we’re really not talking about zero waste.”

With pushback an undeniable consequence of these changes, increased costs will likely arise for businesses selling or distributing food serviceware. But, Sue Sanger, a Councilmember of St. Louis Park underscored that in reality, these businesses are currently “off-loading their costs” and that “They may be saving a little money, but the environment is paying the price and frankly the taxpayers are paying the price. Taxpayers are funding the incinerators, the landfills and so on.” While local businesses in Sanger’s area will only have months to comply for most packaging types, some exemptions are in place for small portion cups and PS lids for the time being. Elsewhere, we can expect cities to reduce the quantity of exemptions and shorten the time periods that using non-recyclable or compostable packaging is tolerated.

Indeed, D.C., Minneapolis, and St. Louis Park’s packaging ordinances will likely serve as a model for other cities looking to move closer to encroaching zero waste goals. For cities that currently have packaging ordinances, we can expect further refinements and tightening of scope. The lessons learned from the smattering of first generation packaging ordinances in all of the cities discussed here will hopefully provide opportunities for improvement in second generation packaging ordinances introduced in coming years. In particular, including food serviceware incidentals like straws, utensils, and stir sticks will make palpable differences in compost manufacturing operations. Similarly, providing more nuanced guidance on what constitutes a recyclable plastic package will go far in ensuring that recyclers are able to collect the highest-value materials that also sort and reprocess correctly. Initiatives likes ASTRX provide guidance for those navigating the recycling system. As cities aim for lasting zero waste solutions, facilitating strong business models for both composters and recyclers is a fundamental that cannot be forgotten.

For those of us working in the sustainable materials management space, we’ve understood for a long time that plastic pollution in the world’s oceans has been a serious problem.

But, for many, the concern reached a zenith when the World Economic Forum shed light on the projection that by weight, there will be more plastic in our oceans than fish by 2050 in the New Plastics Economy Report. With a little over a year since publication, a flurry of activity has surfaced among consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies involving ocean plastic. CPGs have developed numerous initiatives to both source recovered ocean plastic as an input for packaging and several apparel companies have engineered ways of using ocean plastic in textiles for clothing and shoes. Both are strategies that have important challenges worthy of examination, but also show multinational companies are interpreting circular economy principles in new and more diverse ways.

Parley for the Oceans is one organization that has served as a bridge from stakeholders concerned with threats to marine biodiversity and conservation to the private sector, responsible for both generating plastic material that escapes into the environment and providing demand for recovered ocean plastic as an input for new products and packaging. One recent partnership has been between Parley for the Oceans and Adidas, where they designed the Adidas UltraBOOST Uncaged shoe made with a knitted upper comprised of 95% recovered ocean plastic and 5% recycled polyester. While the first 7,000 units were released on November 15, 2016, Adidas Group Executive Board member Eric Liedtke explains that, “We will make one million pairs of shoes using Parley Ocean Plastic in 2017 – and our ultimate ambition is to eliminate virgin plastic from our supply chain.”

Parley for the Oceans is one organization that has served as a bridge from stakeholders concerned with threats to marine biodiversity and conservation to the private sector, responsible for both generating plastic material that escapes into the environment and providing demand for recovered ocean plastic as an input for new products and packaging. One recent partnership has been between Parley for the Oceans and Adidas, where they designed the Adidas UltraBOOST Uncaged shoe made with a knitted upper comprised of 95% recovered ocean plastic and 5% recycled polyester. While the first 7,000 units were released on November 15, 2016, Adidas Group Executive Board member Eric Liedtke explains that, “We will make one million pairs of shoes using Parley Ocean Plastic in 2017 – and our ultimate ambition is to eliminate virgin plastic from our supply chain.”

But Adidas isn’t limiting recovered ocean plastic as a feedstock material for footwear, they also worked with Parley to create the first jerseys made of 100% ocean plastic for football teams Real Madrid and Bayern Munich. Munich player Xabi Alonso (left, in red) highlighted that, “Wearing a [jersey] that is made from recyclable ocean waste is something I’m very happy about as it’s a fantastic opportunity to raise awareness about the need to protect and preserve our oceans.”

Indeed, raising awareness about sustainability in general and ocean plastic pollution specifically is a chief benefit of using recovered ocean plastic in new products and packaging. Method – People Against Dirty was one of the first companies to use recovered ocean plastic in their soap bottles in 2012 and highlighted the importance that social awareness was to their packaging design. Parham Yididsion of Envision Plastics, Method’s recycling partner, explained that it was a project where they could actually make a difference and make a point. This emphasis on awareness and activism emerges in Method founder Adam Lowry’s discussion of the project as well. He elaborates that, “We know that only a small amount of plastic will be taken out of the ocean through all of these bottles. We know that’s not the solution. But, we also know that we can have a much bigger impact if we start to change people’s mind about their role in protecting our oceans.”

Much like Method’s conventional soap bottles that use 100% post-consumer recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET), the ocean plastic bottles designed out the need for virgin plastic, reducing the carbon footprint by 70%. Since Method first broke ground in sourcing ocean plastic to produce plastic bottles, the industry has been innovating to increase the percent of ocean plastic in a given resin mix.

Procter & Gamble, for example, is releasing a limited run of Head & Shoulders shampoo bottles this summer in France at Carrefour stores. P&G’s black high-density polyethylene (HDPE) is unique in that unlike many other ocean plastic packages, they’ve worked to sort-out other polymers from the beach plastic that it sources. In addition, P&G has raised the proportion of ocean plastic in the formulation up to 25%. More generally, the CPG company announced that by the end of 2018, it will have half a billion packages in Europe with at least 25% post-consumer recycled content, among its hair care portfolio including Head & Shoulders and Pantene.

One downside to packaging that employs recovered ocean plastic is that the plastic’s color often results in a dark grey when processed. From this point, many companies will then use dark or black colorants to make the package appear more uniform and provide more juxtaposition with competition on-shelf. When on the sorting line at a MRF however, this results in near-infrared (NIR) sorting technology not being able to distinguish between black polymer types. The Association of Plastic Recyclers (APR) illuminates in their authoritative Design Guide that, “There is no mechanical property inherent in black HDPE that makes it unrecyclable. The problem lies in sorting and the physics behind polymer identification.” The same NIR sorting challenges affect black PET, but unlike HDPE, opaque colored PET does not have an end market even if sorting challenges were overcome.

Another challenge that P&G’s Vice President for Global Sustainability Virginia Helias highlights is the limited quantity of beach plastic and much higher expense due to the complex supply chain of its collection and processing. Critics of ocean plastic use in plastic packaging will point out that this elaborate supply chain also likely means that the environmental toll of transport involved negates some of the benefit to the material recovery. Yet, conservationists are quick to counter that if the material is being collected by volunteers from beaches or waterways already, a second-life as a package or textile is certainly a better outcome than a landfill or incinerator.

Another challenge that P&G’s Vice President for Global Sustainability Virginia Helias highlights is the limited quantity of beach plastic and much higher expense due to the complex supply chain of its collection and processing. Critics of ocean plastic use in plastic packaging will point out that this elaborate supply chain also likely means that the environmental toll of transport involved negates some of the benefit to the material recovery. Yet, conservationists are quick to counter that if the material is being collected by volunteers from beaches or waterways already, a second-life as a package or textile is certainly a better outcome than a landfill or incinerator.

Nevertheless, companies like Adidas using recovered ocean plastic in large quantities incentivize efforts to continue removing plastic from the ocean as they help to coalesce a reliable end market for the material. Dell, which is using 25% ocean plastic in its 100% post-consumer recycled content laptop trays, stress that this is a deliberate aspect to their sustainability initiatives. Dell describes the initiative as the“first commercial-scale global ocean plastics supply chain.” Moreover, the computer technology company, “will convene a working group to address ocean plastics at scale.” In due course, more companies will likely continue to incorporate ocean plastic as a feedstock once a reliable and larger stream of plastic is being recovered from waterways. As Parley for the Oceans Founder Cyrill Gutsch clarifies, “At this point, it’s no longer just about raising awareness.”

No matter where you stand on the issue today, be sure to engage in the conversation during the Sustainable Packaging Coalition’s next Open Forum on March 23rd from 1-2pm EST. Joi Danielson from the Ocean Conservancy and Procter & Gamble’s Jack McAneny will be shedding light on their work in the ocean plastics space. Learn more and register HERE.

A Safer Choice for Pet Care

Pets are an important part of more than half of US households, and pet owners want their furry family members to have a happy and healthy life free from exposure to hazardous chemicals. There is a growing, multi-billion dollar market for pet care products, but it can be challenging for pet owners to get a full understanding of the chemicals of concern in the products they buy, since it is uncommon for products to come with a full ingredient listing.

As a result, these pet care products can be a source of pet exposure to hazardous chemicals. Ingredients of concern may include harsh surfactants that may cause irritation or have carcinogenic effects, or thickening and pearlizing agents with poor environmental toxicity profiles. In some cases, ingredients may be even more of a concern for pets than they are for humans. Many essential oils and plant extracts fall into this category, since they can act as sensitizers when pets are exposed, resulting in allergic reactions.

Pets may also be more exposed to hazardous chemicals from household products because they tend to be smaller and closer to the ground and groom themselves using their mouths. They also have faster metabolisms and smaller lungs than humans, so they breathe in more chemicals from the environment and process them faster. Smaller pets, like rodents and fish, can be especially vulnerable to cleaning products, including products used to clean cages and aquariums. Like humans, pets are susceptible not only to acute poisoning by toxic chemicals, but also to diseases like cancer that can be caused by exposure to hazardous chemicals.

Fortunately, companies in the pet care sector are responding to consumer demand for safer products. Pet owners looking for safer chemicals in the products they use to care for their pets, such as pet shampoo, can now find pet care products bearing the U.S. EPA Safer Choice label on store shelves. Safer Choice is a trusted assurance that certifies products that are safer for people, pets, and the environment, and until now, has been used primarily to label household and institutional and industrial cleaning products. Pet owners can find Safer Choice-labeled products intended to be used directly on pets, such as pet shampoo, as well as cleaning products used in the home, in order to ensure a safe and healthy environment for their pets and the rest of their family. Like all Safer Choice-labeled products, all ingredients in pet care products with the Safer Choice label have been screened by third party profilers and EPA, assuring they are safer for both the environment and human and animal health.

Before making the Safer Choice label available for this new category of products, EPA evaluated conventional chemistries in the pet care sector. They looked at ingredients of pet care products that have been disclosed publicly, and reviewed existing data on the hazards associated with these chemicals. In order to ensure that their standards for pet care products were protective for pets, the Safer Choice team also spoke with stakeholders, including veterinary toxicologists, and conducted research to determine if any of the chemicals used in pet care products are particularly toxic to dogs and cats.

Before making the Safer Choice label available for this new category of products, EPA evaluated conventional chemistries in the pet care sector. They looked at ingredients of pet care products that have been disclosed publicly, and reviewed existing data on the hazards associated with these chemicals. In order to ensure that their standards for pet care products were protective for pets, the Safer Choice team also spoke with stakeholders, including veterinary toxicologists, and conducted research to determine if any of the chemicals used in pet care products are particularly toxic to dogs and cats.

The first products in the pet care category to be labeled with the Safer Choice label are two pet shampoos from ECOS for Pets! by Earth Friendly Products – one fragrance free and one peppermint-scented, currently being sold in pet supply stores and at www.ecos.com. Earth Friendly Products has produced pet care products since it was founded in 1967, but is now better known for its household cleaning products. The company formulates its pet care line to the same safety and sustainability standards as its home care line, because it takes the view that pets deserve the same high standards as the rest of the family when it comes to the chemicals we use on and around them.

Matt Arkin, Director of Pet Sales with Earth Friendly Products, said

“As a long time partner of the Safer Choice program, we were so excited about the opportunity to create ECOS for Pets! and offer the first certified pet products. There are so many options for consumers and just as much confusion as to what green means that making a good decision can be overwhelming. The Safer Choice seal will provide clarity for those who want to make the best choices for their pets’ health. It is the pre-eminent third party certification and consumers can feel confident that ECOS for Pets! was formulated to the most exacting standards.”

The ECOS for Pets! products were not tested on animals, which presented a bit of a challenge for the performance testing required by the Safer Choice program. Instead of testing the performance of these shampoos on live animals, alternative performance tests were developed. With some outside-the-box thinking and the use of many faux fur swatches, Earth Friendly Products was able to complete the performance testing required for the Safer Choice label and ensure the efficacy of its products. Other than this hiccup, the process of obtaining the Safer Choice label on these products was smooth, in large part because the products were already formulated to the Safer Choice program standards.

Because pets roll in mud, track in dirt, shed fur, spill their food and water, and have the occasional accident, pet owners need safe and effective pet care and cleaning products. Because EPA reviews all Safer Choice products to ensure that they are safer for pets, as well as humans and the environment, it is easier for consumers to feel confident that they are making a good decision regarding the products they purchase. Safer Choice-labeled products, including all-purpose cleaners, carpet cleaners, deicers, floor care products, pet stain and odor removers, toilet bowl cleaners, and upholstery cleaners are great options for pet owners to clean up after their pets while also keeping them safe and healthy.

Preservatives are an essential ingredient for most household and personal care products, but can also be a challenge for manufacturers looking to minimize chemical hazards in their products.

Consumers expect the products they buy to maintain quality and usability for months after purchase, if not longer. Microbial contamination can negatively affect both the stability and the performance of a formulation. For example, microbes can generate acidic byproducts that affect the pH of the formulation, potentially reducing cleaning efficacy. Microbial growth can also have aesthetic effects by changing the odor or color of the formulation. Finally, microbial growth can present a health risk for users of the product (particularly for vulnerable populations), and can result in product recalls. To meet consumers’ expectations, the formulation of most household and personal care products requires the use of preservatives to protect against microbial contamination.

The susceptibility of a product to microbial contamination depends on a number of factors. Microbes may be introduced into a product either during the manufacturing process (even when good manufacturing practices are used) or during use of the product by the consumer. Water is essential to the growth of microbes and is present in many household and personal care products, and ingredients in many products (such as surfactants or fragrances) can serve as food for microbes. Microbial growth also depends on a product’s pH; bacteria can typically grow at pH 4 to 9, while fungal growth typically occurs at a pH of 3 to 10. However, microbes can also grow outside this pH range if they are acclimated to a manufacturing environment. Today’s environmentally-friendly products are more likely to be water-based and have lower levels of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and heavy metals, so they are more potentially susceptible to microbial contamination. Plus, use of readily biodegradable surfactants often made from plant sugars can increase microbial activity, increasing the need for preservation.. Because of this susceptibility, preservatives are used in almost all liquid household and personal care products.

A number of preservatives have recently come under scrutiny, with regulatory bans and restrictions as well as consumer, NGO, and retailer pressure to eliminate their use. Examples include the category of compounds known as parabens, which have been criticized as potential endocrine disruptors, and compounds that release formaldehyde, a human carcinogen. In light of the concern consumers have about potentially hazardous preservatives in household and personal care products, businesses are taking note. Companies are taking steps to disclose the preservatives they use — for example, in December 2016 Procter & Gamble released a new preservative tracker, and in recent years Johnson & Johnson took steps to remove parabens and formaldehyde-releasing compounds from certain of its products.

These increasing pressures and restrictions reduce the selection of preservatives available to formulators of household and personal care products.

Some preservatives used in lieu of parabens or formaldehyde-releasing compounds are potentially allergenic, and overuse of these in multiple products can lead to sensitization and allergic reactions.

For example, methylisothiazolinone was named the “Allergen of the Year” by the American Contact Dermatitis Society in 2013, and will be restricted for certain cosmetic applications in the EU in 2017.

As a result, there is a need for manufacturers to identify new, safe, and effective preservatives. Preservatives are by definition toxic to bacteria and fungi, so identifying alternatives that are effective in controlling a broad spectrum of microbes while being non-toxic to humans and the environment is a challenge. Natural alternatives to conventional preservatives, such as essential oils, plant extracts, and organic acids, are sometimes used, and may have more favorable toxicological profiles. For example, a number of organic acids are listed on EPA’s Safer Chemical Ingredient List (SCIL) with a full green circle designation, indicating that they have been verified to be of low concern based on experimental and modeled data. However, these compounds are not appropriate for use as preservatives in all formulations. For example, organic acids are useful at a pH range of 2 to 6 and are effective against fungi and a subset of bacteria. They are not effective against all bacteria and have limited use as preservatives in alkaline products such as all purpose cleaners and laundry detergents. Therefore, broader spectrum preservatives and preservatives effective at an alkaline pH are needed for some formulations, even though in some cases the only suitable options may have some hazard concerns such as the potential for sensitization.

Few new preservatives are currently being developed, due in part to the high cost and regulatory hurdles in place. For example, the EU Cosmetics Regulation bans marketing animal-tested ingredients for cosmetics, requiring alternative safety testing methods which may not be available for all endpoints. In the US, preservatives are regulated as antimicrobial pesticides under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), requiring extensive and costly efficacy and toxicity testing.

The Green Chemistry & Commerce Council (GC3) has recognized the need for new, safer preservatives, and launched its Preservatives Project with two stated goals:

- To accelerate the commercialization of new, safe, and effective preservative systems for personal care and household products; and

- To create a new model of pre-commercial collaboration whereby companies with common needs for new, safe chemicals, materials, or other technologies, can accelerate the development and scale-up of these technologies.

Through this initiative, GC3 has developed criteria for safer preservatives and in 2016 launched a preservatives competition to motivate research and development of safer preservatives. The initiative has earned the support of major retailers such as Walmart and Target, which participate in the organization’s Retailer Leadership Council, as well as a number of chemical manufacturers and manufacturers of household and personal care products hoping to find safer ingredients for their products.

Preservatives remain essential to maintain the quality of most household and personal care products, but are a challenge for companies looking to eliminate hazardous ingredients from their formulations. Chemical suppliers have an opportunity to develop and introduce innovative solutions, since demand for preservatives in products will continue even as consumers become increasingly aware of the hazards posed by many existing preservatives.

To rinse or not to rinse

It is important to properly prepare packaging for recycling in order to optimize the quality of recycled materials, but it can sometimes be confusing. How exactly do we know when it’s necessary to rinse our packaging and when it is more valuable to conserve water?

Determining whether rinsing packaging is necessary depends on a few factors, including how much residue is left, what was in the container, and whether the closure even allows you to easily rinse the inside of the container?

Here are a few guidelines:

Here are a few guidelines:

- If you are making sure that every container is empty before recycling it, you’ve gone most of the way towards being an excellent recycler. Packaging that is still full or partially full is at high risk of being landfilled even if you place it in your recycling bin. You should compost any remaining crumbs or unused food products before recycling.

- Any package containing a lot of thick and sticky residue, like a jar of peanut butter or a tub of icing, should be rinsed.

- Any package containing soap (dishwasher detergent, shampoo, laundry detergent, hand soap, etc.) should not be rinsed. In fact, some plastic recyclers rely on residual soap to clean the plastics during reprocessing. After all, it is important to reduce, reuse, and recycle!

- Rinsing does not need to be perfect. Don’t worry about getting every single spot of residue off, because that uses a lot of water. Just splash that salsa jar with a little water, replace the lid, and it’s ready to go.

- If the cap or lid isn’t easily removed for you to get inside it and rinse, don’t worry; just make sure the package is thoroughly empty before recycling.

Look for the How2Recycle label that explains when a container should be rinsed or not. When in doubt, use your best judgment: a high quality, low contaminant recycling stream is important, but so is water conservation.

Lessons from TAPPI’s Introduction to Pulp and Paper Technology

There are two words that can describe the papermaking process: fascinating and complicated. Paper products are fundamental to our everyday lives, but how often do we actually think about how it is made? Prior to joining GreenBlue, the answer to that question for me, was never. When most of us think about paper, we think about forests and trees: where the paper comes from.

I had the privilege of recently spending four, eight-hour days participating in TAPPI’s Introduction to Pulp and Paper Technology short course. TAPPI is a professional organization dedicated to the pulp and paper industries. It was during this course that I got an in-depth look at the pulp and papermaking.

I had the privilege of recently spending four, eight-hour days participating in TAPPI’s Introduction to Pulp and Paper Technology short course. TAPPI is a professional organization dedicated to the pulp and paper industries. It was during this course that I got an in-depth look at the pulp and papermaking.

If you ever thought pulp and papermaking was a simple process, think again! Pulp and paper are developed through a soup of chemical, physical and mechanical processes. While it is relatively easy to sum up the function of each part of the process, as soon as you go beneath the surface, things get a lot more interesting and complicated.

The course is taught by Dr. Mike Kocurek, one of the world’s most recognized educators in the pulp and paper industry. Dr. Kocurek was inducted into the Paper Hall of Fame over a decade ago, and he’s taught TAPPI’s Intro to Pulp & Paper course for over 33 years. Dr. Kocurek continues to be a great instructor exhibiting a level of knowledge that most can only hope to obtain in a lifetime.

Day One: Dr. Kocurek opened up the day with a light intro on state of the industry, highlighting global market trends and statistics. Following this, the real content began with a discussion on the raw material used for papermaking: wood fiber. Different species of trees – hardwoods/softwoods – pulp differently from one another and as such have implications on the paper properties. After trees have been harvested, their first stop is the woodyard to be debarked, chipped, and then cooked in pressurized vessels called digesters. Another way to think about this process is to think about cooking pasta, first you start with the hard noodles, then you cook it until it’s soft and ready to eat. Only in this process, you cook the wood fiber in a medley of chemicals to make pulp.

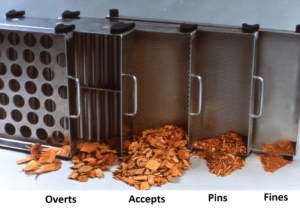

Our activity of the day involved sorting out a wood chip pile into the various chip quality categories, which can be seen in the image below. We spent the second half of the afternoon with an overview of the pulping process, where we primarily learned about the Kraft process, the dominant pulping method in North America.

Day Two: Our second morning began with a segway into pulp processing and bleaching. Before pulp can be turned into the beautiful, bright white color, it must first be processed by washing, screening, and cleaning it. After being processed it is then time for the bleaching process. Initially facilitated by chlorine chemicals, during the 1980s scientists began detecting chlorinated compounds in fish downstream from paper mills. Given the health risks of such toxins, the industry phased out their use of chlorine. Today, the dominant method is Elemental Chlorine Free (ECF).

We spent the afternoon exploring paper recycling, which provides approximately the United States with 50% of its total fiber. This topic was particularly interesting in how it relates to our work as an environmental nonprofit, in recent years it’s been interesting to see that with the proliferation of single stream recycling and overall increases in recovery, the quality of the paper recycling stream has suffered from contamination, making high quality recovered fiber a commodity in high demand.

Day Three: This can also be referred to as “the day that went over my head”. We opened up the morning with a discussion on paper grades and properties, followed by the next step in the process: stock preparation and forming. Stock prep and formation is a multi-step process that involves a lot of big machines and a lot of mechanical engineering. Of course, this is all very interesting and relevant for those involved in papermaking operations. However, while it is possible to get basic grasp on the topic, safe to say it’s something probably best left to the chemists and engineers!

Day Four: Our final day began with the pulp being fully prepped and ready to be pressed, dried and rolled into paper. While this process, like the others, is highly technical, it is evermore fascinating. After the stock has been prepared and formed, it is still full of water, so then it needs to be pressed together and dried. These are massive machines, to give you an idea.

It’s from these massive machines that the paper you have sitting on your desk comes from today. After the paper has been dried and rolled, it is then ready to be shipped out and/or converted into any kind of paper product imaginable ranging from a magazine to a corrugated box.

After completing this 32-hour course, my knowledge of papermaking went from being basically a general idea of the process, to being conversant on a technical level.Additionally, as I was sitting in the Tampa airport waiting to board my flight home I realized that, while I was leaving a work event, it felt more like leaving a group of friends. Every day after the training sessions, I had the opportunity to engage with mill-level industry employees which was both enjoyable and enlightening experience.

I would highly recommend the Introduction to Pulp and Paper Technology course to anyone who is looking to get a look under the hood of pulp and papermaking operations. Despite having almost no background knowledge in this field, Dr. Kocurek presents the information in a digestible way that, even for the most novice of attendees, is still relevant and useful. In addition to this course, TAPPI offers a wide range of continuing education programs for everyone in the pulp and paper industry, click here to view the events calendar for 2017.

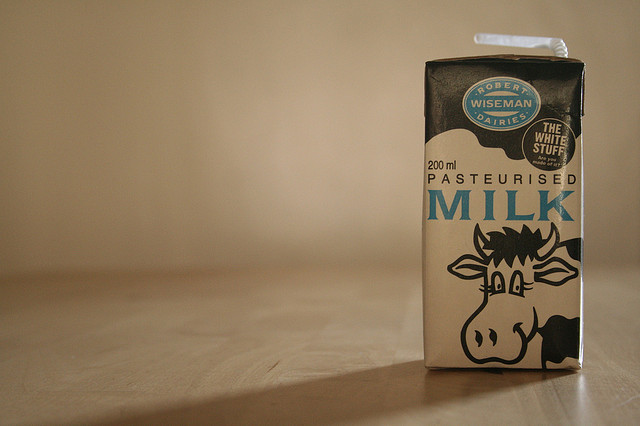

Not everything is recyclable, and for most unrecyclable packaging, the supremely-coveted designation cannot be obtained without achieving the impossible: creating systemic change within an economically-stressed establishment full of inertia and wary of anything that isn’t a conventional “core” recyclable. The Carton Council did just that, and their replicable method deserve applause.

Acceptance in recycling programs is often measured by examining the instructions given to consumers, so it would seem logical to encourage municipalities to include the item in their recycling instructions and one day declare that the item is accepted enough to be called “recyclable.” This is not what the Carton Council did. The correct way to improve an item’s recyclability is to start three steps beyond collection and work your way back. That means starting with end markets.

Acceptance in recycling programs is often measured by examining the instructions given to consumers, so it would seem logical to encourage municipalities to include the item in their recycling instructions and one day declare that the item is accepted enough to be called “recyclable.” This is not what the Carton Council did. The correct way to improve an item’s recyclability is to start three steps beyond collection and work your way back. That means starting with end markets.

First stop: the end market. Without demand from end markets, recycling falls apart. Somebody actually has to want the material, meaning they have to be able to do something with it in an economically-viable way, and this potentially obvious aspect of recycling is too often ignored. The Carton Council addressed this first, working with recycled paper mills to understand how they could utilize the fibers in used aseptic and gabletop cartons and helping them optimize their systems to do so.

Armed with confidence that recovered cartons have a final destination, the next stop is one step back: recycling commodity brokers and the specifications used to sell recovered paper products. Because now that cartons have a destination, they need to get there. Most bale specifications for fiber products were crafted to be applicable to an average mill. Cartons, though, don’t fit with the repulping capabilities of an average mill. Only a select few can process them. A new bale specification was needed. Grade #52 was born, and the path to those select few mills became paved a bit more.

Second stop: Material recovery facilities identify and sort recyclable packaging by unique physical characteristics, and there was not an established sorting method to recover cartons. The exploited physical characteristic of most paper items is their flatness, but cartons, or course, are not flat. The Carton Council had to work with material recovery facilities to identify novel techniques of automated identification and sortation to get those cartons out of a mixed recycling stream and into those grade #52 bales sent to those select few mills. They did that.

Third stop: sortation. It’s time to address the issue of acceptance in collection programs. This part is easy when the last steps are addressed first. When a municipality can be told that their sorting facility can process the material and sell it on the commodity market, why wouldn’t they include the item in their list of accepted recyclables?

The Carton Council has done a tremendous job transforming an unrecyclable item into a recyclable one.. But the work is far from done. Now that cartons are recyclable, we need to see them recycled, because it’s never enough to put a recyclable package on the market and wash your hands of the recycling challenge. So it is with admiration that we celebrate the Carton Council’s accomplishment, and anticipation for other industry groups to replicate their success.